Originally published on 25 February, 2018

Revised on 2 December, 2021

Revised on 2 December, 2021

Introduction

This blog outlines historical features of the monetary regime cycle in an attempt to contemplate the forthcoming monetary paradigm [1].

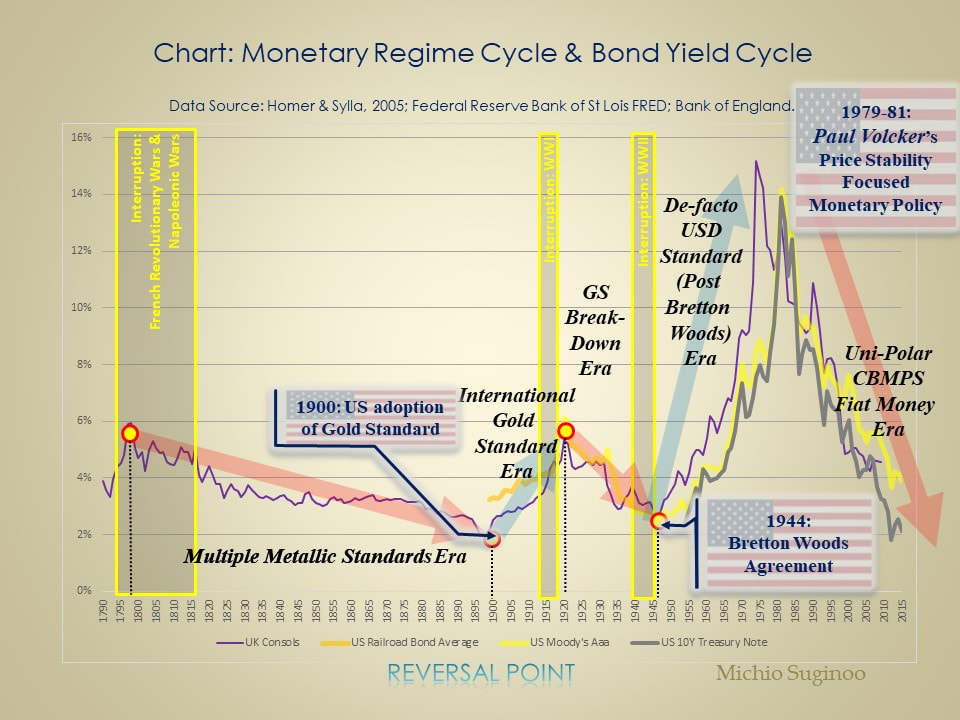

Since the 19th century, the monetary system has transformed from metallic standards to fiat money. In its passage, the paradigm shifts in monetary regime took place around the reversal of the bond yield cycle (call it the bond wave) in the core global power states—namely UK until the early-20th century and US thereafter [2].

As another relevant fact, historical reversals of the bond wave demonstrates some sort of correlation tendency with extreme monetary conditions, either with some lags or nearly in synchs. A top range of bond yield cycle is highly associated with an extreme inflationary environment; its bottom range, with an extreme deflationary environment, except for war interruption periods. [3] (Suginoo, 2017)

These two empirical facts suggest that extreme monetary conditions might have something to do with paradigm shifts in monetary regime.

Now, the hype of cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, dictate news of our time, partly reflecting frustrations against fiat money, the existing monetary system under central bank’s dominance. This trend has also emerged in line with the evolution of the current deflationary environment among some advanced economies. When we follow history as a guide, this coincidence—an extreme monetary condition and frustrations against the existing monetary regime—casts a notion of a new paradigm shift in monetary regime.

Refraining from analysing the causal relationship between these factors—monetary conditions, bond yield cycle, and monetary regime cycle—this reading invites readers to focus on observing historical facts as a guide to formulate relevant and legitimate questions about the present and the future of our monetary paradigm. In this attempt, it sees that our reality is driven by at least three dynamics: cyclical dynamics, evolutionary dynamics, and by-product of accidents. In a way, it promotes an agnostic approach in economic thinking, without heavily relying on any particular school of economic thought.

Now, I would like to begin with historical analogy to derive a pattern of cyclical dynamics, thereafter, contemplate underlying evolutionary dynamics.

Throughout this writing, I use the following three expressions associated with the core power states of time—namely UK during the 19th century and the three decades of the 20th century and USA thereafter—interchangeably: the cycle of long term bond yields, bond yield cycle, and the bond wave.

Now, the hype of cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, dictate news of our time, partly reflecting frustrations against fiat money, the existing monetary system under central bank’s dominance. This trend has also emerged in line with the evolution of the current deflationary environment among some advanced economies. When we follow history as a guide, this coincidence—an extreme monetary condition and frustrations against the existing monetary regime—casts a notion of a new paradigm shift in monetary regime.

Refraining from analysing the causal relationship between these factors—monetary conditions, bond yield cycle, and monetary regime cycle—this reading invites readers to focus on observing historical facts as a guide to formulate relevant and legitimate questions about the present and the future of our monetary paradigm. In this attempt, it sees that our reality is driven by at least three dynamics: cyclical dynamics, evolutionary dynamics, and by-product of accidents. In a way, it promotes an agnostic approach in economic thinking, without heavily relying on any particular school of economic thought.

Now, I would like to begin with historical analogy to derive a pattern of cyclical dynamics, thereafter, contemplate underlying evolutionary dynamics.

Throughout this writing, I use the following three expressions associated with the core power states of time—namely UK during the 19th century and the three decades of the 20th century and USA thereafter—interchangeably: the cycle of long term bond yields, bond yield cycle, and the bond wave.

Cyclical Dynamics:

Historical Patterns in Paradigm Shift of Monetary Regime

Now let’s get a big picture of empirical cyclical dynamics by walking through historical facts below along the chart of bond yield:

1) Multiple Metallic Standard Era:

During the early 19th century, there were several clusters of distinct metallic standard among major economies. No single metallic standard played a core central role to integrate the global monetary order. The United Kingdom was under the gold standard; German speaking states were under the silver standard; other major states including France were under the bimetallic standards. This regime coincides with a long declining-wave of the bond wave.

After its victory of the Franco-Prussian war in 1871, the newly unified German Empire, replacing its legacy silver standard with the monetary system of UK. This, creating the network externality of the gold standard, incentivised the rest of the advanced economies to converge into the gold standard. US’ adoption of the gold standard in 1900 completed the convergence process among major economies.

Arguably this century can be divided into two parts: a pure multiple metallic standards era before the unification of German Empire in 1871; and the international convergence period thereafter, during which major currencies converged into the gold standards.

During the early 19th century, there were several clusters of distinct metallic standard among major economies. No single metallic standard played a core central role to integrate the global monetary order. The United Kingdom was under the gold standard; German speaking states were under the silver standard; other major states including France were under the bimetallic standards. This regime coincides with a long declining-wave of the bond wave.

After its victory of the Franco-Prussian war in 1871, the newly unified German Empire, replacing its legacy silver standard with the monetary system of UK. This, creating the network externality of the gold standard, incentivised the rest of the advanced economies to converge into the gold standard. US’ adoption of the gold standard in 1900 completed the convergence process among major economies.

Arguably this century can be divided into two parts: a pure multiple metallic standards era before the unification of German Empire in 1871; and the international convergence period thereafter, during which major currencies converged into the gold standards.

2) International Gold Standard Era:

As a result of the earlier convergence movement, major economies’ monetary system was integrated into the gold standards, in which London market predominantly played a core central role in organising the international monetary order.

During the period between 1900 to 1913, the major advanced economies operated their monetary system under International Gold Standard: it, with the interruption period of WWI, corresponds to the short rising bond wave 1900-20.

As a result of the earlier convergence movement, major economies’ monetary system was integrated into the gold standards, in which London market predominantly played a core central role in organising the international monetary order.

During the period between 1900 to 1913, the major advanced economies operated their monetary system under International Gold Standard: it, with the interruption period of WWI, corresponds to the short rising bond wave 1900-20.

3) Breakdown Era of Gold Standard:

The interwar period between the end of WWI and the outbreak of WWII corresponds to the breakdown era of the gold standard; it coincides with a declining-wave of the bond wave.

Under intensifying economic difficulties, the post WWI world experienced a series of compromises and suspensions in the conduct of the gold standard. The international monetary system broke down, while authorities failed to present a viable replacement until the Bretton Woods Agreement. The agreement coincides with the bottom of the bond yield cycle.

During this period UK made a series of abortive attempts to restore its legacy monetary system, the gold standards.

The interwar period between the end of WWI and the outbreak of WWII corresponds to the breakdown era of the gold standard; it coincides with a declining-wave of the bond wave.

Under intensifying economic difficulties, the post WWI world experienced a series of compromises and suspensions in the conduct of the gold standard. The international monetary system broke down, while authorities failed to present a viable replacement until the Bretton Woods Agreement. The agreement coincides with the bottom of the bond yield cycle.

During this period UK made a series of abortive attempts to restore its legacy monetary system, the gold standards.

4) De-facto USD Standard Era:

The post-WWII reconstruction period was another phase of failure of fixed exchange rate. It took a gradual multiple-step shift. In retrospect, this post-WWII period placed USD in the monopoly position of the key currency. It coincides with the rising bond wave of 1945-1981.

The post-WWII reconstruction period was another phase of failure of fixed exchange rate. It took a gradual multiple-step shift. In retrospect, this post-WWII period placed USD in the monopoly position of the key currency. It coincides with the rising bond wave of 1945-1981.

- In the aftermath of WWII, the Bretton Woods System was designed as a variant of the gold-exchange standard, which allowed central banks to substitute foreign exchange reserves for gold reserves. By its statute, the Bretton Woods System did not prohibit the gold convertibility of non-USD currencies. Nevertheless, it transformed to a de-facto gold-USD standard because of economics as the rest of the world demanded USD as gold-reserve substitutes because of the US’s predominant economic position.

- Under intensifying economic difficulties with inflation, in 1971 the Nixon Shock, the unilateral abolition of USD gold convertibility, unveiled the de-facto USD standard.

- Thereafter, under the Smithsonian Agreement, USD became subject to speculative attacks. In 1973, when US devalued USD by 10% against the value of gold, due to speculative market pressures, major currencies went float. In practice, 1973 marks a milestone in the official acknowledgement of a fiat currency world.

- UK Consols Yield peaks in 1974 and makes reversal thereafter. On the other hand, US Bond Yields continues to surge further and waits its reversal until the debut of Paul Volcker as the new Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank.

- Volcker’s monetary policy with a special attention to price stability during 1979-1981, which took the form of federal funds rate hikes, led to the reversal of the bond wave. In a way, Volcker’s action not only demonstrated the final official acknowledgement of fiat money by the central bank, but also set the new standard for the new fiat money regime, by placing central bankers’ price stability policy as the primary anchor in monetary affair. To illustrate the novelty of Volcker’s approach, in the conventional monetary affair during metallic standards era, underlying metallic value was considered as the primary anchor to equilibrate key economic variables in theory, while monetary authorities’ policy action was deemed secondary: whether this theoretical notion is true or not in practice is debatable.

- The peace-time transition from metallic standards to fiat money regime started in the aftermath of WWI finally made its conclusion with Volcker’s monetary policy paradigm shift: it took two bond waves, one declining bond wave between 1920 and 1945 and the other rising one between 1945 and 1982.

Revision Announcement (2 December, 2021)

The original description regarding the Bretton Woods System was misleading. Thus, the following revision was made.

- Original Statement: “In the aftermath of WWII, the vacuum of power in the Old Continent allowed US to assume a monopoly power in the Bretton Woods Conference to experiment ‘de-facto USD standard regime,’ in which USD was the only currency convertible to gold and the rest of currencies were loosely pegged to USD. This arrangement significantly compromised the metallic convertibility of currencies and marked the first step toward fiat money regime.”

- Revised Statement: "In the aftermath of WWII, the Bretton Woods System was designed as a variant of the gold-exchange standard, which allowed central banks to substitute foreign exchange reserves for gold reserves. By its statute, the Bretton Woods System did not prohibit the gold convertibility of non-USD currencies. Nevertheless, it transformed to a de-facto gold-USD standard because of economics as the rest of the world demanded USD as gold-reserve substitutes because of the US’s predominant economic position"

5) Uni-polar, Central Bank's Monetary Policy Standard Fiat Money Era:

The period after 1982 until today operated under fiat money regime. It has a special set of characteristics below:

These empirical facts suggest a cyclical dynamics: monetary regime transitions nearly coincided with reversals of the bond wave. In other words, monetary regime cycle nearly synchronised with the bond yield cycle

The period after 1982 until today operated under fiat money regime. It has a special set of characteristics below:

- Volcker's move in the late 1970s was a strong political statement that the new standard for the new fiat money regime, by placing central bankers’ monetary policy with a special attention to price stability as the primary anchor in monetary affair. In other words, the new monetary regime is not merely fiat money, but also "Central Bankers' Monetary Policy Standard (CBMPS)."

- During the era, USD plays a ‘uni-polar’ role in the international monetary order: it served as the sole predominant key reserve currency and the nearly sole common unit of account for international transactions, in which the prices of major commodities and international services are priced in USD.

- Overall, the monetary system during this period can be characterised as “Uni-Polar, CBMPS Fiat Money System” under USD dominance.

These empirical facts suggest a cyclical dynamics: monetary regime transitions nearly coincided with reversals of the bond wave. In other words, monetary regime cycle nearly synchronised with the bond yield cycle

Evolutionary Dynamics:

The historical cyclical patterns also revealed three salient evolutionary features:

Now, living under the historically low bond yields environment, we are either supposedly approaching or already around the bottom reversal of the bond wave (this might be proven wrong, if a persistent deflation were to re-emerge going forward). If history is a guide, we are likely to experience some sort of paradigm transformation in the monetary regime—potentially with some time lag. In this perspective, we are compelled to ask a relevant and legitimate question: what sort of transition could take place at the next reversal of the bond wave.

- Developments from the multiple metallic standards paradigm in the 19th century to the current uni-polar fiat money paradigm demonstrates a persistent trend of integration—with some potential interruptions (i.e. the breakdown era of the gold standard during 1920-1944).

- It demonstrated another persistent evolutionary trend from fixed exchange rate systems to fiat money.

- Monetary regime cycle is shaped by geopolitical factors as well as economic factors;

Now, living under the historically low bond yields environment, we are either supposedly approaching or already around the bottom reversal of the bond wave (this might be proven wrong, if a persistent deflation were to re-emerge going forward). If history is a guide, we are likely to experience some sort of paradigm transformation in the monetary regime—potentially with some time lag. In this perspective, we are compelled to ask a relevant and legitimate question: what sort of transition could take place at the next reversal of the bond wave.

Transitions:

Paradigm Shifts of Monetary Regime

The monetary regime cycle in the chart, providing only four historical reversals of the bond wave, presents at least three types of monetary transitions: two ‘orderly transitions,’ a ‘chaotic transition,’ and a ‘total vacuum.’

1) Orderly transition to a new paradigm:

Two ‘orderly transitions’ evolved along new consolidation stages in the global geopolitical order:

1) Orderly transition to a new paradigm:

Two ‘orderly transitions’ evolved along new consolidation stages in the global geopolitical order:

- International convergence to gold standards between 1871 and 1900: During the early 19th century, UK was the only state operating the gold standard. After its victory of the Franco-Prussian war in 1871, the newly unified German Empire made its decision to replace its legacy silver standard with the monetary system of UK. [4 ] This, triggering the network externality of the gold standard, incentivised the rest of the advanced economies to adopt the gold standard.

- Shift to 'De-facto USD Standard' at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944: A year before the end of WWII, the vacuum of power in the Old Continent allowed US to assume a monopoly power in the Bretton Woods Conference to experiment ‘de-facto USD standard regime.’ In its backdrop, the breakdown of the gold standard had lasted throughout the inter-war era, in the absence of a viable monetary regime replacement.

2) Chaotic transition to a new paradigm:

A chaotic transition of monetary system can be characterised by an episode from an earlier historic event, the birth of UK gold standard, which emerged as a by-product of arbitragers’ victory against the monetary authority at that time, Sir. Isaac Newton, the Master of Mint and the founder of deterministic thinking, Newtonian Physics.

-

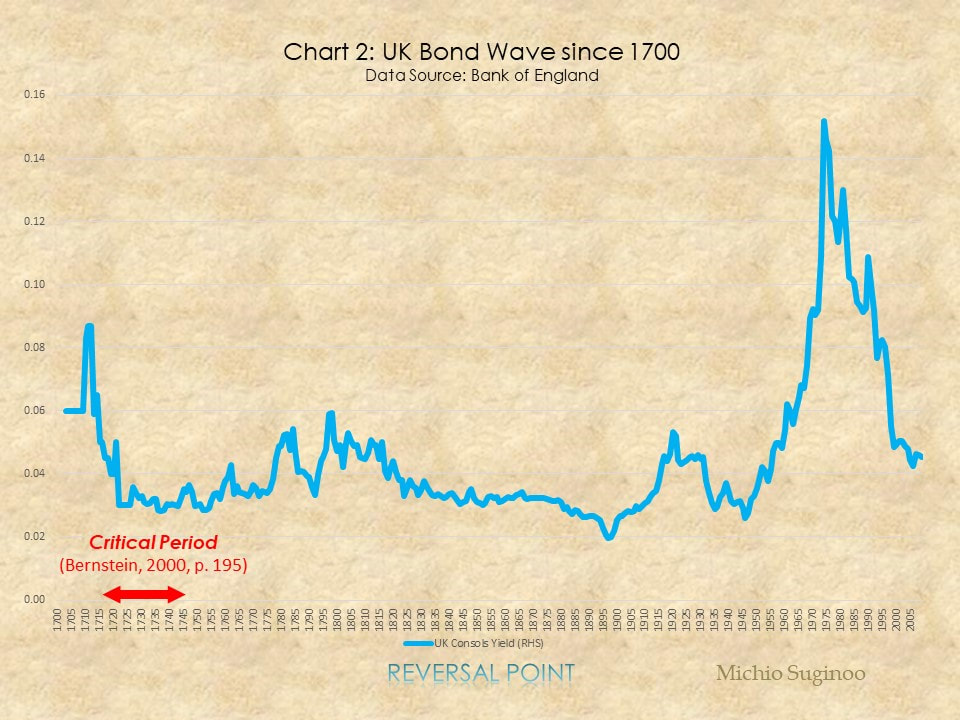

The birth of UK gold standard: The birth of UK gold standard was a by-product of the central authority’s failure in operating its bimetallic standards. Although this transition took a long path for about a century, the critical part progressed within thirty years since 1717 [Note 5] (Bernstein, 2000). Chart 2 below locates the critical period, which coincided with the bottom range of the bond wave. The story evolved against the will of the monetary authority at that time, Isaac Newton, the master of the Mint. The founder of the Newtonian physics was a prominent believer of determinism. In economic reality, where uncertainty can predominantly dictate, Newton’s deterministic approach turned out to be fatal in managing bimetallic standards, which operates with two metallic monies, gold and silver coins. Due to his deterministic thinking, he failed to capture the uncertain economic dynamics of exchange rate between silver coins and gold coins. Cut the long story short, his deterministic fixed exchange rate setting between these two metallic monies created a profitable opportunity for arbitragers to export silver coins out of UK. When the majority of silver coins disappeared from UK, the UK metallic standard was primarily left with gold coins: as a result, it turned out to be a de-facto gold standard. It was symbolical that later, John Maynard Keynes, who incorporated uncertainties into economic thinking, made a remark about Newton, the determinist: "Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians, the last of the Babylonians and Sumerians, the last great mind which looked out on the visible and intellectual world with the same eyes as those who began to build our intellectual inheritance rather less than 10,000 years ago." (Keynes, n.d.)

Here is another case:

3) Total Vacuum: breakdown with no new replacement:

This vacuum scenario is a variant of chaotic transition. The difference is the absence of a new regime for replacement throughout the entire life of an era. This dire scenario is exemplified by the inter-war period between the end of WWI and the beginning of WWII.

Both types, ‘chaotic transition’ and ‘vacuum,’ illustrate the unwillingness and inability of authorities to cope with new economic realities: monetary authorities’ inertia to trap themselves in a counter-productive deterministic mind setting to preserve the legacy regime that would no longer serve new economic realities. Here, as the common part of these two stories, is a self-defeating paradox: their deterministic pursuit rather caused economic imbalances and impaired their existing monetary paradigms. As a result, they failed to command an orderly transition to present a new monetary regime. These episodes illustrate that new regimes could emerge as the by-products of arbitragers’ victory against monetary authorities’ inertia.

So far, we observed three types of monetary regime transition: orderly transitions; chaotic transitions; a total vacuum (breakdown of legacy regime without any new replacement).

What type would emerge in the next transition? In order to anticipate the type of the next transition, we need to monitor both the ability and the willingness of our monetary authorities in coping with forthcoming uncertainty.

Here are a few takeaways. In contemplating the next monetary transition, we need to consider the following points:

- The shifts from 'De-facto USD standard' to 'Uni-polar CBMP standard': The post-WWII reconstruction period was another phase of failure of fixed exchange rate and took a gradual disorderly shift to floating exchange rate. This transition has taken place in multi-steps since the creation of the Bretton Woods System, which substantially compromised the gold bullion standard at its inception. Then, the Nixon Shock in 1971 and USD devaluation in 1973 followed. Meanwhile, arbitragers responded with a series of speculative attacks to repudiate the existing rigid monetary regime and concluded with their decisive victory, float of major currencies. The state of disorder lasted until the new FRB Chairman, Paul Volcker set the new standard for the emerging fiat money regime.

3) Total Vacuum: breakdown with no new replacement:

This vacuum scenario is a variant of chaotic transition. The difference is the absence of a new regime for replacement throughout the entire life of an era. This dire scenario is exemplified by the inter-war period between the end of WWI and the beginning of WWII.

- Breakdown era of the gold standard: The interwar period experienced a series of compromises and suspensions in the conduct of the gold standard. The international monetary system broke down, while authorities failed to present a replacement until the Bretton Woods Conference. During this period, UK made a series of abortive attempts to restore its legacy monetary system, the gold standards.

Both types, ‘chaotic transition’ and ‘vacuum,’ illustrate the unwillingness and inability of authorities to cope with new economic realities: monetary authorities’ inertia to trap themselves in a counter-productive deterministic mind setting to preserve the legacy regime that would no longer serve new economic realities. Here, as the common part of these two stories, is a self-defeating paradox: their deterministic pursuit rather caused economic imbalances and impaired their existing monetary paradigms. As a result, they failed to command an orderly transition to present a new monetary regime. These episodes illustrate that new regimes could emerge as the by-products of arbitragers’ victory against monetary authorities’ inertia.

So far, we observed three types of monetary regime transition: orderly transitions; chaotic transitions; a total vacuum (breakdown of legacy regime without any new replacement).

What type would emerge in the next transition? In order to anticipate the type of the next transition, we need to monitor both the ability and the willingness of our monetary authorities in coping with forthcoming uncertainty.

Here are a few takeaways. In contemplating the next monetary transition, we need to consider the following points:

- geopolitical developments;

- both the ability and the willingness of our monetary authorities to present a new monetary paradigm to cope with new economic realities;

Toward the Future:

Contemplating New Monetary Paradigm

Now, given the cyclical pattern and the evolutionary dynamics underlying historical monetary regime cycle, we can contemplate our future: potential scenarios for the next monetary regime, taking into account geopolitics, innovation, and general economics.

Among many possibilities, we can contemplate the scenarios below.

a) Change in the key currency within the existing framework of fiat money CBMPS regime:

b) Crypto-currency

Innovation could trigger evolutionary dynamics in either way: a further integration or a reversal to disintegration. ‘Network externalities’ dynamics might trigger a new convergence to a particular crypto-alternative beyond the border. Or on the contrary, distributed systems might shape a new trend toward a plurality among multiple key cryptocurrencies: therefore, a disintegration.

Crypto-currency class can present the following potential scenarios, at least.

c) Regress to commodity monetary standard.

Either a return to a metallic standard or a new experiment in a basket of commodities standard casts a notion of a reversal toward fixed exchange regime, thus, a reversal in the evolutionary dynamics of the monetary regime cycle.

It might require us to listen to lessons from our history. Fixed exchange rate regimes did not work in practice in the past: actually, it does not work theoretically either. Also, remember ‘Boar War,’ in which states fought in pursuit for gold, the metallic resource for monetary expansion. What a depressing scenario.

d) Blend of multiple forms of currency:

As a possibility, we might face a situation in which multiple forms of currency mediums—e.g. fiat money, P2P cryptocurrencies, CBCC, metallic moneys—operate simultaneously. Although it might not be a main scenario, we cannot exclude a possibility that multiple forms of currency co-exist and shape a new form of monetary regime. This might evolve into either a chaotic transition or a total vacuum.

e) Breakdown Era of Fiat money:

As we observed during the inter-war era between WWI and WWII, this is a ‘total vacuum’ scenario. Like the earlier episode, central bankers of our time, trapped in an inertia to preserve the existing paradigm and unable to present a new monetary paradigm, might be causing economic imbalance and instability, which ultimately would fail the current paradigm and create a vacuum.

There should be more. I welcome suggestions from readers.

Ending Remarks:

Now, we have incorporated cyclical dynamics and evolutionary dynamics into our anticipation of the future monetary regime.

Why these things are relevant to us?

Now, living under the historically low bond yields environment, we are supposedly around the bottom reversal of the bond yield cycle (this might be proven wrong, if a persistent deflation were to re-emerge going forward). If history is a guide, we are likely to experience some sort of paradigm transformation in the currency regime—maybe with some time lag.

Contemplating the type of the next regime, we need to monitor both the ability and the willingness of our monetary authorities in coping with forthcoming uncertainty.

Among many possibilities, we can contemplate the scenarios below.

a) Change in the key currency within the existing framework of fiat money CBMPS regime:

- “Multi-Polar Fiat Money CBMPS System (CBMPS: Central Bankers' Monetary Policy Standard)”: a shift to have multiple key currencies within the existing fiat money regime: for example, tri-polar world of EUR, USD, and RMB. This would interrupt the persistent evolutionary trend for integration or even make a supra-secular reversal towards disintegration.

- “A Polar-shift in Uni-Polar CBMPS Fiat Money System”: a polar-shift of the key currency position to another major currency from USD: for example, a polar shift from USD to RMB. This scenario is in line with the persistent evolutionary trend for integration. That said, which currency can create its own network externality to replace USD? Yet to be seen.

b) Crypto-currency

Innovation could trigger evolutionary dynamics in either way: a further integration or a reversal to disintegration. ‘Network externalities’ dynamics might trigger a new convergence to a particular crypto-alternative beyond the border. Or on the contrary, distributed systems might shape a new trend toward a plurality among multiple key cryptocurrencies: therefore, a disintegration.

Crypto-currency class can present the following potential scenarios, at least.

- Central Bank Issued Cryptocurrencies (CBCC): After struggling through a deflationary environment, central bankers might embrace a new innovation to enable themselves to universally apply negative interest rates. Currently, under the fiat money regime, the possibility of cash hoarding makes it impossible for them to apply negative interest rates universally across the economy—including private saving rates (Suginoo, 2016). By digitizing money, CBCC, central bankers can universally apply negative interest rates. There are theoretical variations in CBCC. In an extreme scenario, when society abandons the need of privacy in retail transactions, a central bank can deploy a centralised (vs. peer-to-peer) digital monetary system which operates only through central bank’s accounts (Bech & Garratt, 2017). This extreme model might eliminate the necessity of retail banks (Brett, 2017).

- Peer-to-peer Cryptocurrencies (P2PCC): Alternative to the centralized system is peer-to-peer cryptocurrencies (P2PCC), such as Bitcoin. It is operated by so-called “permission-less, public blockchain” (Blockchainhub.net, ND). Needless to say, the beauty of Bitcoin is that it enables peer-to-peer monetary model to operate in the absence of a centralised government. But the catch is that, because of the absence of a centralised trusted party, the validation process suffers from a trilemma: it cannot meet three desirable goals at the same time—high scalability (fast transaction speed and larger volume of transaction), low physical cost (energy consumption and computational power), and integrity of the system’s security (Suginoo, 2018). To illustrate this point, as an example, as of February 18, 2018, the annualised energy consumption of Bitcoin is comparable to the annual energy consumption of Portugal. And it is increasing every day. On this matter, we need to keep monitoring Digiconomist’s “Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index”: https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption (De Vries, 2018). As a result, P2PCC is not a sustainable solution yet as of today. For P2PCC to become a full-fledged monetary regime, it would require a breakthrough in its trust-building mechanism called consensus protocols to solve the trilemma issue as a necessary condition, if not sufficient one.

- Hybrid alternative: A hybrid system, which is expected to be more energy efficient than pure P2PCC, might emerge. Some CBCC models contemplate peer-to-peer features for retail transactions (Barrdear & Kumhof, 2016, pp. 7-8; Bech & Garratt, 2017).

c) Regress to commodity monetary standard.

Either a return to a metallic standard or a new experiment in a basket of commodities standard casts a notion of a reversal toward fixed exchange regime, thus, a reversal in the evolutionary dynamics of the monetary regime cycle.

It might require us to listen to lessons from our history. Fixed exchange rate regimes did not work in practice in the past: actually, it does not work theoretically either. Also, remember ‘Boar War,’ in which states fought in pursuit for gold, the metallic resource for monetary expansion. What a depressing scenario.

d) Blend of multiple forms of currency:

As a possibility, we might face a situation in which multiple forms of currency mediums—e.g. fiat money, P2P cryptocurrencies, CBCC, metallic moneys—operate simultaneously. Although it might not be a main scenario, we cannot exclude a possibility that multiple forms of currency co-exist and shape a new form of monetary regime. This might evolve into either a chaotic transition or a total vacuum.

e) Breakdown Era of Fiat money:

As we observed during the inter-war era between WWI and WWII, this is a ‘total vacuum’ scenario. Like the earlier episode, central bankers of our time, trapped in an inertia to preserve the existing paradigm and unable to present a new monetary paradigm, might be causing economic imbalance and instability, which ultimately would fail the current paradigm and create a vacuum.

There should be more. I welcome suggestions from readers.

Ending Remarks:

Now, we have incorporated cyclical dynamics and evolutionary dynamics into our anticipation of the future monetary regime.

Why these things are relevant to us?

Now, living under the historically low bond yields environment, we are supposedly around the bottom reversal of the bond yield cycle (this might be proven wrong, if a persistent deflation were to re-emerge going forward). If history is a guide, we are likely to experience some sort of paradigm transformation in the currency regime—maybe with some time lag.

Contemplating the type of the next regime, we need to monitor both the ability and the willingness of our monetary authorities in coping with forthcoming uncertainty.

In the modern context, one relevant note here is Shirakawa’s monetary policy paradox: monetary policy, in its very pursuit for creating economic stability, can create wrong incentives among economic agents to engender economic imbalance and economic instability. Monetary policy’s success in containing inflation can feed very causes of financial crisis—an extension of leverage and its consequence, asset bubble. In the long run, monetary policy could merely end up transferring economic imbalance from one area to another in the economy. Ultimately, monetary policy loses its effectiveness. This dynamics is endogenous and creates a self-defeating cycle. (Suginoo, 2017) [6] We might be witnessing a precursor for the next monetary regime transition.

After all, we still need to be aware of our limitation in contemplating the future: two dynamics—evolutionary dynamics to a great extent and by-product of accidents—are tautologically beyond our ability to anticipate. That said, with this simple agnostic framework, we might still be able to learn a lot from the past.

After all, we still need to be aware of our limitation in contemplating the future: two dynamics—evolutionary dynamics to a great extent and by-product of accidents—are tautologically beyond our ability to anticipate. That said, with this simple agnostic framework, we might still be able to learn a lot from the past.

Notes

[Note 1] Throughout the series, ‘cycle’ refers to general pendulum-like oscillation dynamics with irregular periods and irregular vertical scale. It is an open system that is susceptible to cyclicality, evolutions, and uncertainties. Therefore, it does not convey any notion of a regular periodic constant cycle.

[Note 2] The bond wave is only associated with the core power states of time—namely UK during the 19th century and the three decades of the 20th century and USA thereafter—referring to either of the followings: the cycle of its long-term bond yields in a general context, and a rising cycle of its long-term bond yields or a declining cycle of its long-term bond yields in a trend context.

[Note 3] A war interruption can cause inflationary force even at the bottom of the bond yield cycle. (Goldstein, 1988, pp. 252-253) As an example, the post-Great-Depression deflationary environment was transformed to be inflationary by WWII even at the bottom of the bond yield cycle at that time.

[Note 4] Henry Kissinger (2014) wrote “Disraeli called the unification of Germany in 1981 “a greater political event than the French Revolution” and concluded that “the balance of power has been entirely destroyed.” The Westphalian and the Vienna European orders had been based on a divided Central Europe whose competing pressures—between the plethora of German states in the Westphalian settlement, and Austria and Prussia in the Vienna outcome—would balance each other out. What emerged after the unification was a dominant country, strong enough to defeat each neighbour individually and perhaps all the continental countries together. The bond of legitimacy had disappeared. Everything now depended on calculations of power. (…) Europe’s new order was reduced to five major powers, two of which (France and Germany) were irrevocably estranged from each other.” (Kissinger, 2014)

[Note 5] “The process [of arbitrage] persisted, in fact, about thirty years, beyond 1717, by which time full-weight silver coins had disappeared from circulation.” (Bernstein, 2000, p. 195)

[Note 6] Shirakawa’s paradox reminds us of Hyman Minsky’s emblematic phrase “Stability is Destabilising” that encapsulates his Financial Instability Hypothesis. Both Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis and Shirakawa’s Monetary Paradox share the same topic—causes and consequences of finance-fed financial crises. While Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis has intense focus on the private sector’s money creation mechanism, Shirakawa’s Monetary Policy Paradox has a wider framework to examine and question the effectiveness of central banks’ monetary policy actions. And both articulate that policy incentives and behaviours and psychologies of economic agents play significant roles in altering economic reality. (Suginoo, 2017)

References

- Barrdear, J., & Kumhof, M. (2016, July). The macroeconomics of central bank issued digital currencies. London: Bank of England. Retrieved 2 20, 2018, from bankofengland.co.uk/: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/working-paper/2016/the-macroeconomics-of-central-bank-issued-digital-currencies

- Bech, M., & Garratt, R. (2017, September 17). Central bank cryptocurrencies. Retrieved from BIS.org: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1709f.pdf

- Bernstein, P. L. (2000). The power of gold: the history of an obsession. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Brett, C. (2017, September 29). The BIS "Money Flower" expanded. Retrieved from Enterprise Times: https://www.enterprisetimes.co.uk/2017/09/29/the-bis-money-flower-expanded/

- BlockchainHub.net. (ND). Blockchains & Distributed Ledger Technologies. Retrieved from BlockchainHub.net: https://blockchainhub.net/blockchains-and-distributed-ledger-technologies-in-general/

- De Vries, A. (2018, February 18). Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index. Retrieved 2 18, 2018, from Digiconomist: https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption

- Eichengreen, B. (2008). Globalizing capital: a history of the international monetary system (Second edition ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Eichengreen, B. (2011). Exorbitant Privilege. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goldstein, J. S. (1988). Long cycles: prosperity and war in the modern age. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Keynes, J. M. (n.d.). Newton, the man. Retrieved from http://phys.columbia.edu/~millis/3003Spring2016/Supplementary/John%20Maynard%20Keynes_%20%22Newton,%20the%20Man%22.pdf

- Kissinger, H. (2014). World Order: reflections on the character of nations and the course of history. New York: Penguin Press.

- Suginoo, M. (2017, November 19). BOND WAVE MAPPING: CASE STUDY 1: Paradigm Transformations in International Monetary System Along the Bond Wave. Retrieved 2 20, 2018 from ReversalPoint.Com: http://www.reversalpoint.com/bond-wave-mapping-1-paradigm-transformation-in-interntional-monetary-regime.html

- Suginoo, M. (2017, July 11). BOND WAVE MAPPING: CASE STUDY 2: Price & Inflation Cycles along the Bond Wave. Retrieved2 20, 2018 from ReversalPoint.Com: http://www.reversalpoint.com/bond-wave-mapping-2-price--inflation-cycles.html

- Suginoo, M. (2017, August 30). Shirakawa’s Monetary Policy Paradox (Part I): General Perspective: Architecture of Monetary Policy Paradox. Retrieved 2 20, 2018, from www.reversalpoint.com: http://www.reversalpoint.com/shirakawas-paradox-part-1.html

- Suginoo, M. (2018, February 9). Confusing Blockchain, Chapter 2: Limitations in Consensus Protocols. Retrieved 2 20, 2018 from www.reversalpoint.com: http://www.reversalpoint.com/chapter-2-limitations-in-consensus-protocols

- Suginoo, M. (2017, June 15). THE SECULAR RHYTHM OF THE BOND WAVE: Secular Macro Behavioural Dynamics of Political Economy-Its Indisputable Uncertainty and Irregularity & Equally Undeniable Pendulum Recurrent Dynamics. Retrieved 2 20, 2018 from www.reversalpoint.com: http://www.reversalpoint.com/secular-rhythm-of-bond-wave.html

- Suginoo, M. (2016, December 8). Zero Boundary of Nominal Interest Rate. Retrieved 2 20, 2018 from www.reversalpoint.com: http://www.reversalpoint.com/zero-boundary.html