Shirakawa’s

Monetary Policy Paradox (Part II)

Particularities in Empirical Monetary Policy Paradox:

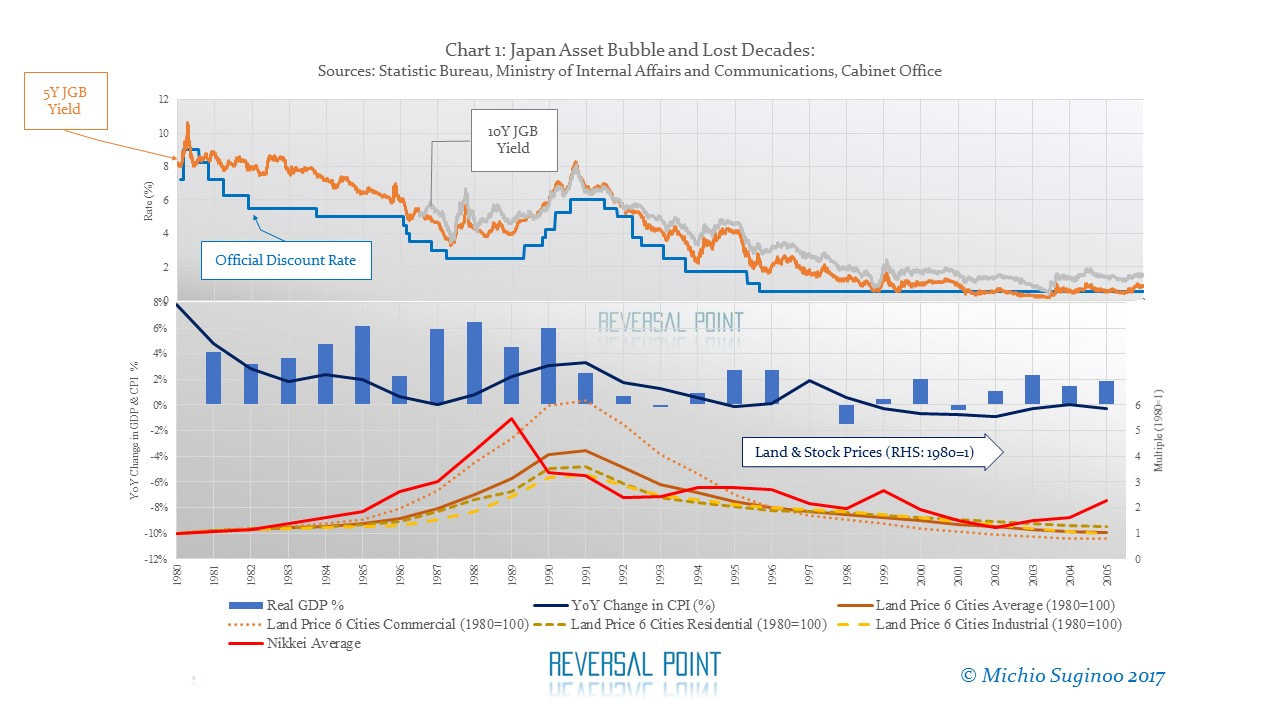

Japan’s Experience (1980s-2000s)

Originally published August 28, 2017

Edited August 30, 2017

By Michio Suginoo

Edited August 30, 2017

By Michio Suginoo

|

The previous reading visited Shirakawa’s past statements and made an overview on the architecture of Shirakawa’s Monetary Policy Paradox: how the monetary policy paradox unfolds from a victory to its self-defeating consequence. It provides us with a general economic perspective of the monetary policy paradox.

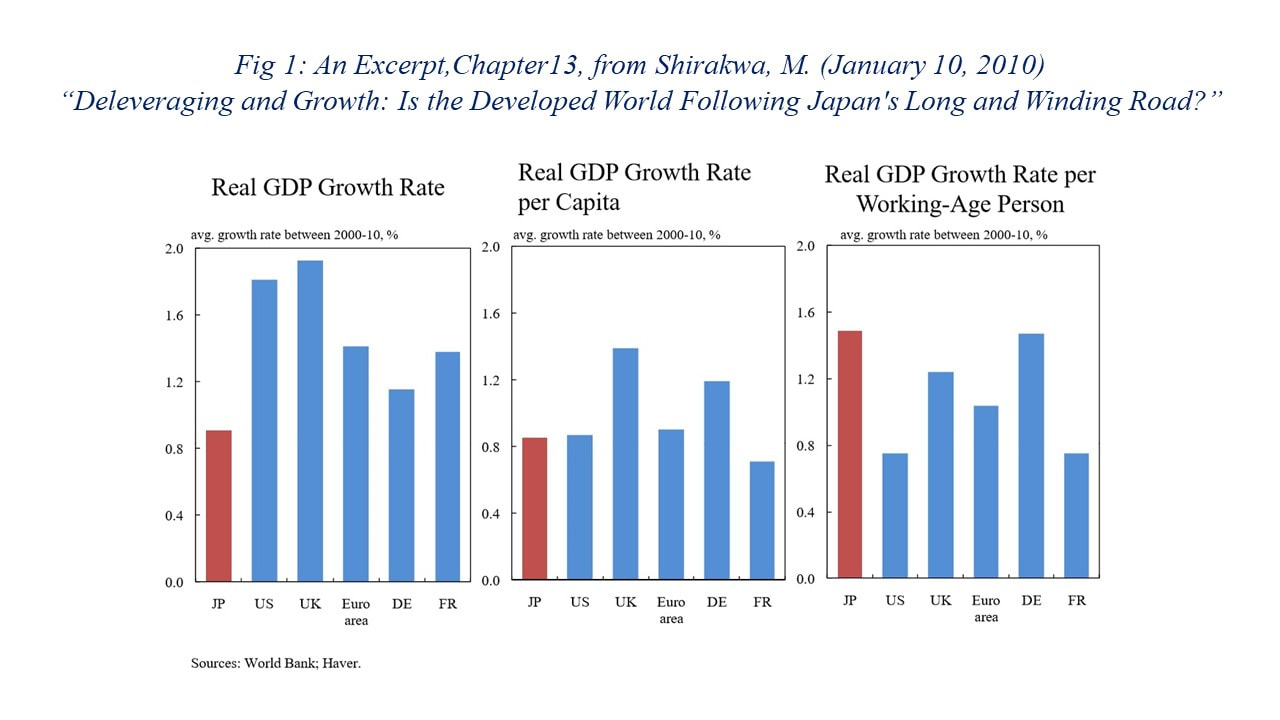

However, in reality, a particular set of conditions could alter the course of economic events and create a particular path for an unfolding financial crisis in the aftermath of a bubble burst. Particularity might be present in economic, social and political conditions. Particular foreign demands can alter the domestic economic conditions. Policy responses are influenced and constrained by particular social and political conditions. Those particularities could significantly differ from one country to another and from one period to another. In order to better analyse each case of financial crisis, it is imperative for us to distinguish between the general architecture of Shirakawa’s Monetary Policy Paradox and a particular set of relevant conditions that each case imposes. Empirical study on specific historical experiences can provide materials for us to understand how particular conditions can shape the course of events along the general architecture of monetary paradox. This reading examines Shirakawa’s Paradox from an empirical point of view. It attempts to observe evidences of the paradox along the empirical chronology of a specific historical experience of Japan during the period between the 1980s and the 2000s. [1] An Empirical Chronology:

|