Series: Zeitgeist Zero Hour

Originally published: June 24, 2019

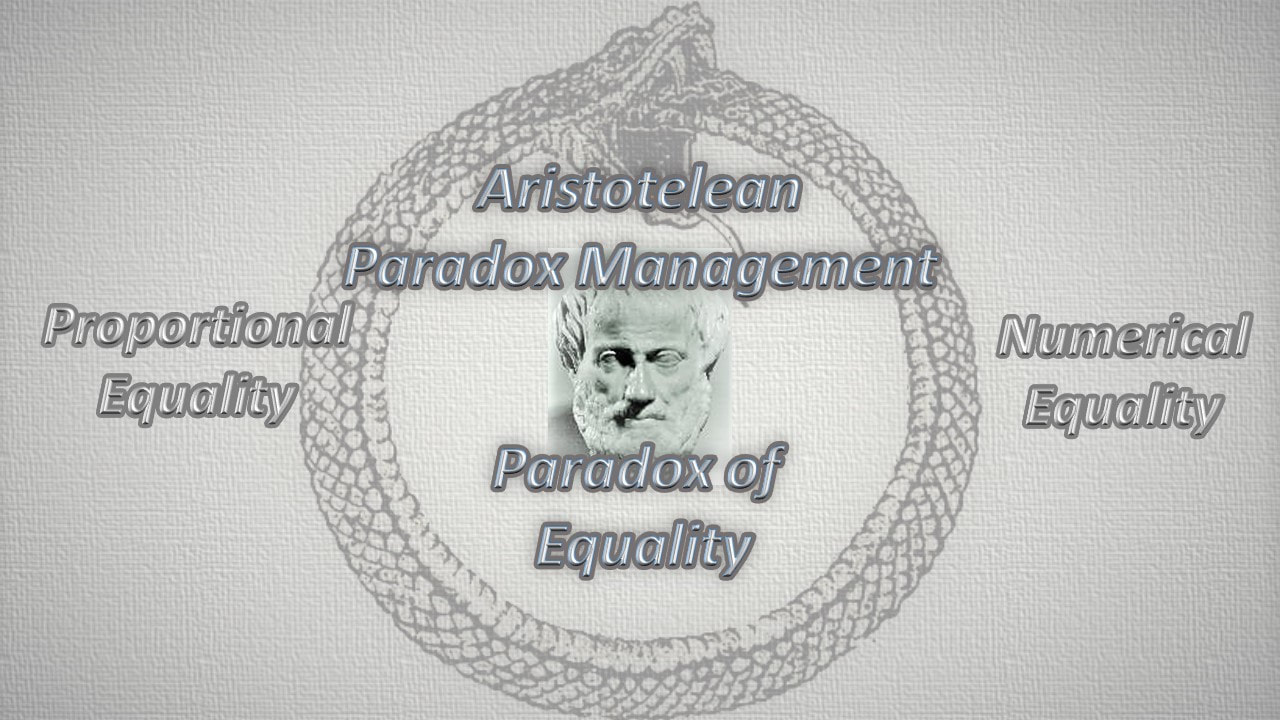

Last edited: July 3, 2019 By Michio Suginoo Aristotle saw paradox in democracy. According to him, the paradox emerges from the general notion of equality, one of the primary principles of democracy. He illuminated how two distinct principles of equality--numerical equality and proportional equality—confront each other and destabilise democracy. In his view, a destabilising cause of democracy is embedded in the very architecture of democracy. He further articulated that the paradox can be managed to preserve democracy.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the world of paradox that we live in. In Chapter 1, Socrates [1] diagnosed an enigmatic terminal symptom of democracy—democracy is destined to degenerate into tyranny. And the majority ruling, one of the operating principles of democracy, plays a fatal role in giving rise to demagogues to facilitate the ominous transition.

How did Aristotle see Socrates’ fatalistic diagnosis of the terminal symptom of democracy? Is the cataclysmic change in constitutional order (political regime) ‘'a grandeur of ‘historical necessity’’ [2] ? Against fatalism, can we preserve democracy? If possible, how?

Aristotle, in contrast to Socrates, embraced a non-deterministic view. [Click the link for the Contrast between Socrates and Aristotle] He perceived that any constitutional order can be better than a state of chaos such as anarchy and explored possibilities to preserve any given operating constitution, including democracy in antiquity. Can we apply Aristotle’s wisdoms in preserving our contemporary democratic reality? What different approaches would our democracy demand? The question, “Can we preserve democracy?”, is examined by two chapters. Chapter 2, divided into two parts, seek inspirations from the ancient wisdom of Aristotle in addressing constitutional breakdown. And Chapter 3 contemplates our contemporary democratic reality: Part 1 of Chapter 2 intends to sketch distinctive characteristics of Aristotle’s arguments and is divided into the following two sections:

Then, Part 2 of Chapter 2 outlines Aristotle’s general principles and guidelines for the preservation of constitutions and his view on how to preserve democracy of his time. Chapter 3 shifts our focus to our contemporary liberal representative democracy and reflect two intellects of our time, Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), a Holocaust survivor and Jewish German American thinker, and Angie Hobbes the Professor of the Public Understanding of Philosophy at University of Sheffield. Section 1:

|

Copyright © 2019 by Michio Suginoo. All rights reserved.