Series: Zeitgeist Zero Hour

Originally published: June 24, 2019

Last edited: July 1, 2019 By Michio Suginoo Introduction

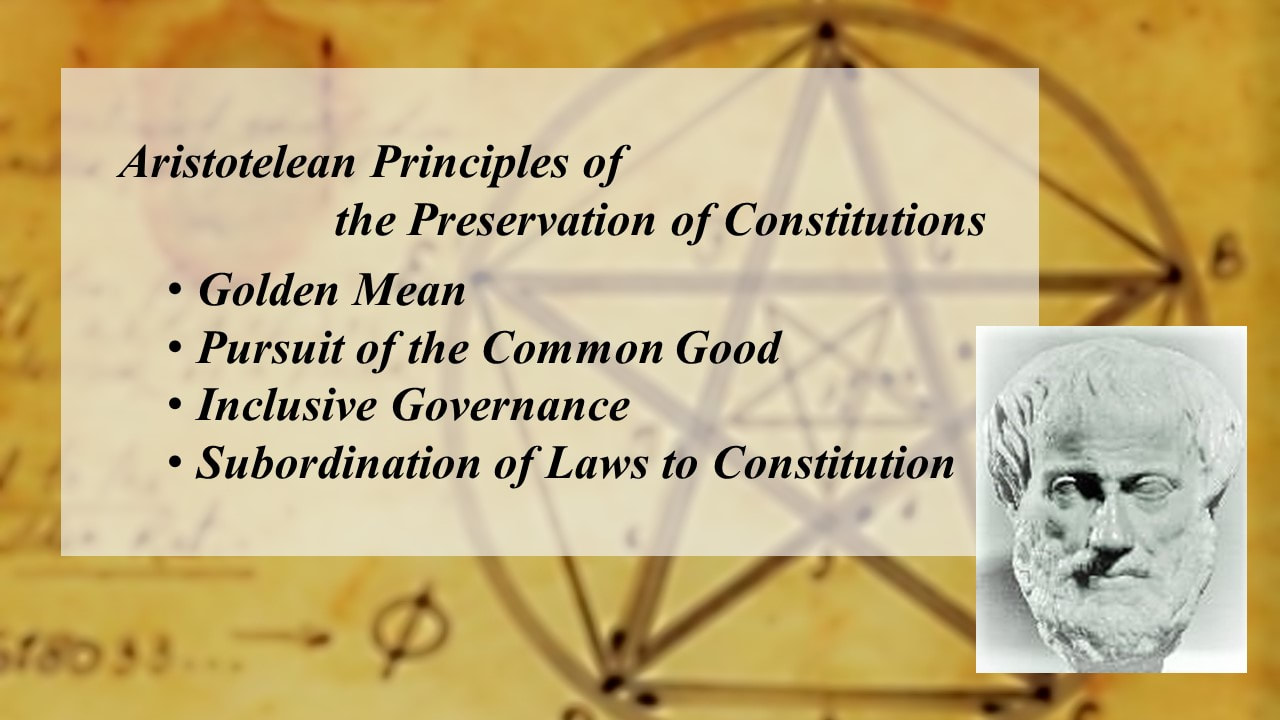

To Aristotle, political chaos—e.g. civil wars, revolution, and anarchy—is the ultimate villain. In this respect, Aristotle’s mind is intensively preoccupied with ‘the prevention of the worst case scenario’. As a result, his preoccupation—to avoid political chaos—shapes his pluralistic view about a good government: any form of constitutional order can be far much better, if not the best one, than a state of chaos. In this light, he explored possibilities to preserve any given constitution.

Precautionary Remark on ‘Class Analysis’

Before we begin, here I would like to make an important precautionary remark. Aristotle, like Socrates, used ‘class-based analysis,’ or ‘class analysis,’ in his discourse: he divided a society into several social classes—the wealthy, the poor, and the middle class, for example. To our contemporary mind, ‘class analysis’ has a strong attachment to Marxist doctrine. Nevertheless, as a historical fact, it was not Karl Marx who started ‘class analysis’. In this context, Aristotle should be deemed dissociated from Communism, simply because Aristotle does not particularly endorse it; he rather promotes individual’s active participation in political activities.

Section 1:

|