Series: Zeitgeist Zero Hour

Originally published: June 24, 2019

Last revused: August 13, 2019 Last edited: August 13, 2019 By Michio Suginoo If democracy were the mother of liberty and equality, toward the end of her life, she would conceive in her matrix (uterus) the foetus of tyranny, demagogues, to ultimately defeat herself. Tyranny—the regime of fierce terror—would be the direct offspring of the most cherished regime of freedom and equality, democracy.

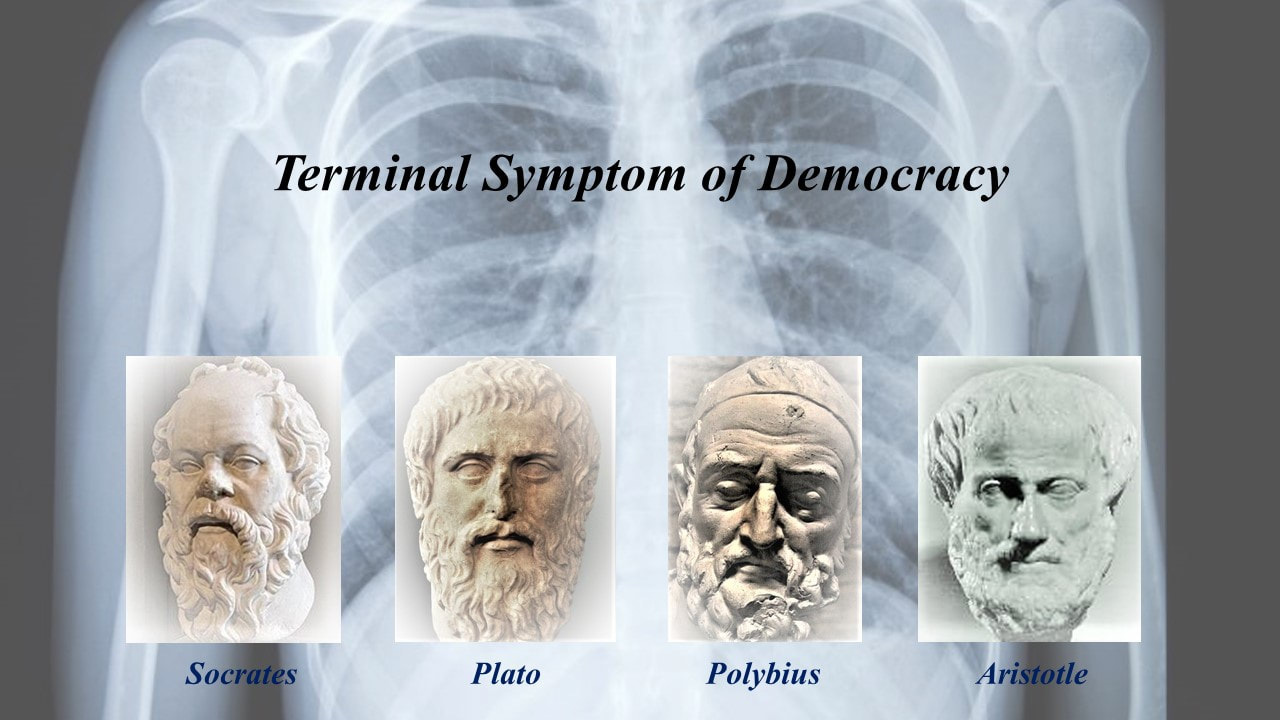

This is my figurative sketch of the terminal symptom of democracy diagnosed by pre-eminent intellects in antiquity—Socrates, Plato, and Polybius. In more plain words, to their eyes, democracy is doomed to degenerate into either tyranny or ochlocracy (mob rule); and the rise of demagogues is an omen for the paradigm shift. To me, as a spoiled beneficiary of democracy, the ancient intellects’ view on the terminal symptom of democracy definitely would sound nothing but an irony and a paradox, should it have even a grain of truth. As a matter of fact, the list of ‘democracy sceptics’ continues further into the age of modernity and includes the following figures: paradoxically some of the founding fathers of the United States (e.g. James Maddison and Alexander Hamilton), and Alexis de Tocqueville. Overall, democracy—which to the eyes of these sceptics is infested with cognitively impaired, or unexamined, opinions—appeared a wrecked state of social order, which is doomed to degenerate into a highly unfree society, tyranny or ochlocracy (mob rule). Each of them perceived logical paradox embedded in the architecture of democracy in one way or another. For example, Alexis de Tocqueville, the 19th century French aristocrat, encapsulated one of the paradoxes of democracy in the simple term ‘Tyranny of the Majority,’ meaning that the majority in democracy, unrestrained, can behave like an absolute monarchical tyrant, override laws and inflict injustice on minorities. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the world of paradox that we live in. How does it manifest anyway? Is it a part of the inevitable process of the life cycle of a grandeur corpse, the Western civilisation? Can we intervene the process? And how to revert the process? Against the ominous implication, from the ancient Greek world, Aristotle provides us with some hope. He proposed some general principles and guidelines to preserve existing constitutional orders of his time. Nevertheless, social norms in antiquity were so different from ours. We cannot simply apply his ancient wisdoms to our contemporary setting. In this light, we need to incorporate our contemporary setting into our thinking and avoid anachronism. This series--"Zeitgeist Zero Hour: Can we preserve democracy?"—contemplates the risk of democratic political order from both the ancient perspectives and our contemporary ones. And it is divided into the following chapters:

Now, this reading, Part 1 of Chapter 1, intends to put our theme, the terminal symptom of democracy, into a perspective. It will paint a synoptic sketch on the ancient notion of democracy that two prominent intellectuals in antiquity—Polybius and Plato’s fictional Socrates in his masterpiece, ‘the Republic’—perceived, then make a contrast with Aristotelian alternative view. As a precautionary note, in portraying democracy, these intellects in antiquity contemplate Athenian democracy, which is direct democracy. On the other hand, most of our contemporary democracy are liberal representative (thus, indirect) democracy—such as ‘presidency representative system’ and ‘parliamentary representative system’. Thus, there is a gap between Socrates’ democracy and our contemporary democratic reality. We need to keep it in our mind in order to avoid anachronism. Section 1: Polybius’ view on Terminal Symptom of Democracy

Little less than three centuries after the life of Socrates and Plato, the Greek statesman and historian Polybius (circa 200-118 B.C.) reflected Socrates’ view on democracy to shape his view on democratic reality. His brief analysis on democracy is very reminiscent to the views conceived by Socrates.

Polybius portrays democracy as a state of highly corrupted political reality. In his view, once a democratic society takes for granted the fundamental operating principles of democracy—equality and freedom—the new generations become sloppy about, or cease to value, those precious special rights—e.g. voting rights, freedom of speech, and other civil rights—that their previous generations risked their life to fight for. As a result, in Polybius view, some seek to create privilege for themselves, thus inequality for the rest, through illegitimate means, e.g. bribery and favouritism. This leads to a highly corrupted state of political order. And the corrupted democracy further degenerates into a regime based on violence. Here, Polybius describes his view on how democracy becomes degenerated into a corrupted political reality:

Simply put, he attributes the breakdown of democracy to corruption.

Section 2: Socrates/Plato’s view on Terminal Symptom of Democracy

The genealogy of Polybius’ narrative on highly corrupted democracy goes back to Socrates (circa 470-399 B.C.). About a little less than three centuries prior to Polybius (circa 200-118 B.C.), Socrates shaped his insight on democracy much deeper than the one that Polybius described.

Zeitgeist, the Soul, of Socratesian Democracy

Socrates’ dialectic discourse brilliantly captures ‘inherently corrupting [1]’ nature of social moral order (psyche). And Socrates reveals that political order can disintegrate from within along social moral decay, even without any interruption of external threat. And, to him, democracy is not an exception.

Socrates defines political order in his unique way. He defines it as an incarnation of the soul—or social moral order, psyche--of an epoch, or Zeitgeist if you like. Moreover, he also illustrates how political order is shaped and destroyed by the transformation of social moral order. Devising his Tripartite Doctrine of the Soul, Socrates first defines three components of social moral order, the soul—reason, appetite, and thumos (a blanket term that encompasses pugnacity, enterprise, passion, spirit, anger, indignation, ambition, and contentiousness. (Lee, 2007, pp. 63, 140-141)). Then, he constructs his version of a perfect soul, in which reason is enshrined on the top and regulates appetite and thumos, and lets it decay uninterruptedly. In this way, he illustrates how the uninterrupted endogenous social moral decay could express a chain of different souls, Zeitgeist, in five phases (or epochs/generations) throughout one life cycle of civilisation (Western Civilisation). Along this process, for each epoch (generation) he populates a distinct political order (constitution) as an incarnation of each Zeitgeist (the soul of epoch). Overall, his constitutional (political regime) cycle—call it Socrates Constitutional Cycle or Socrates Cycle—is an incarnation of its underlying cycle of Zeitgeist. In Socratesian construct of the soul, democracy comes in the 4th phase (epoch) of Socrates Cycle. And it enshrines freedom and equality—in other words, a fully bloomed ‘appetite’—on the top and perverts ‘reason’ in the moral hierarchy of its soul. On one hand, Socrates describes democracy as the most attractive of all political regimes because of “liberty and freedom of speech in plenty”, and “the diversity of its characters” (Plato, the Republic, 2007, pp. 292-293: Book VIII: 557b-c); on the other, he also criticizes it as “an agreeable anarchic form of society, with plenty of variety, which treats all men equal, whether they are equal or not.” (Plato, the Republic, 2007, p. 294: Book VIII: 558c) Political Order of Socratesian Democracy

In principle, the ruling class of democracy is all the citizens. In practice, nevertheless, its sovereign belongs to whoever shapes a majority, since the majority ruling dictates the decision-making process of democracy.

Socrates portrays democracy as a regime of political battleground between the rich and the poor. And he attributes the political divide to a specific class, which he calls ‘drone,’ which is comprised of highly corrupted individuals who live on other peoples’ wealth. In our contemporary setting, ‘drone’ is analogous to politicians and their supporters (e.g. lobbyist and corrupted partisan journalists and intellects) in our contemporary vocabulary. They play a central role of an acting agent in instigating, for their own benefit, confrontations and creating factions between these two opposing ends of social, economic, and political interests. Some work for the rich, the other for the rest. As the system transfers wealth from the rich to the poor, the rich organise themselves to assemble an oligarchy within democracy. Democracy ends up subsuming oligarchy within. In a way, democracy becomes a sort of a crossover multi-verse regime, in which democracy and oligarchy co-exist and competing against each other, in principle. In reality, for the most part of democracy, the oligarchic faction dominates the political battleground, since they are amassed with financial resources and better-organised. Overall, in democracy everyone—the drone, the ordinary, the rich—are after own personal benefit at the expense of the common good, dictated by appetite of the Socratesian democratic soul. As result, all the classes get corrupted in one way or another. The ordinary wants equal social benefit and rights as the wealthy. The wealthy wants special privilege proportional to their qualifications—be it property qualification, birth, or merit. Aristotle called the former ‘numerical equality’ and the latter ‘proportional equality’. It is a paradox of equality (for a summary on Aristotle’s Paradox of Equality: Paradox of Equality and Aristotelean Paradox Management). As a result, all the classes get corrupted. I would interpret and expand further his views into our contemporary context as follows: Politicians and their supporters (e.g. lobbyist and corrupted partisan journalists and intellects), positioning themselves near the logistic of the redistribution system, ignite and amplify the flares of conflict among all social classes—especially, they are divided into two directions: one to the side of the Wealthy, the other to the multitude working class. Some politicians are successful in managing the government in order to do favours for the Wealthy (‘Regulatory Capture’). Partisan supporters on both sides craft ‘Fake News’ to deceive the public. In one way or another, all of them engage in spreading misinformation and disinformation to escalate the tension between the two classes. To Socrates, democracy must have appeared the age of corruption, the age of misinformation/disinformation and the age of degradation of knowledge. The multitude are cognitively impaired by ‘Fake News’. [My opinion statements in Italic in this paragraph] As a historical irony, Socrates himself fell prey to Fake News in the twilight of Athenian democracy. Due to his distorted public image which had been crafted by a comedy play, ‘the Clouds,’ of a prominent poet of his time, Aristophanes, Socrates faced a trial based on groundless accusations. As result, with two charges—of corrupting the youths of Athens; and of blasphemy against Greek Gods—he was sentenced to death. The giant of supreme Wisdom (knowledge and reason), Socrates, in a way succumbed to the ignorance of democracy. His death symbolises the wicked curse of cognitively impaired democratic knowledge, which is crafted based on distorted public consensus, but not based on ‘Reason’ or truth. Zeitgeist: Terminal Symptom of Socratesian Democracy

Political order gets rotten from its head: moral depravity deepens at the ruling class. And the ruling class of democracy is a majority, whatever it might be; but, here we make the general assumption that the majority is the working class.

Socrates implies the issue of widening inequality. That said, inequality existed even in worse forms in previous regimes—timocracy and oligarchy; or even in his utopian ‘just kingship/aristocracy’ equality was not guaranteed. In this sense, Socrates implies something beyond inequality. Something has changed since the emergence of democracy. It is due to change in the moral hierarchy. Now, the ‘appetite’ of democracy, insatiable freedom and equality, rises on the top of its moral hierarchy of the soul and perverts ‘reason’. An extreme freedom would take the society to perfect anarchy and lawlessness. Paradoxically, relentless pursuit for freedom among the working class, Socrates articulates, ultimately provokes an inevitable reaction of reversal to its contrary notion on the opposite end, extreme servitude. (Plato, the Republic, 563 e). Despite this asymmetric backdrop, the poor demonstrate their interest in politics only when they see their economic benefit. Nevertheless, politicians push the majority’s animosity toward oligarchy to the limit. Now, a new kind of leader emerges, by crafting his/her political capital in a unique sort of way. The new leader behaves in disguise of the champion of the working class, by attacking the oligarchs as the common enemy for the largest class of the society. Basically, the new leader is a special sort of populist, a demagogue: simply put, the new leader is typically, if not always, unconventional, inexperienced, and unprincipled in politics, thus, they seek their primary political capital in the common enemies of the majority. The majority elect a single political representative as their champion and provide him/her bodyguards (private army) as well as overwhelming support. (Plato, 565 c, 566 b). In early days of the demagogue, he/she smiles at the working class, pretending to act as their champion and making hints of populist policies, such as debt relief and subsidies (wealth redistribution). (Plato, 566 d-e). In substance, he/she is ‘a Master of Deception’.

As the champion attacks on the wealthy and domesticates the minds of his constituents, the demagogue commits a series of unconstitutional and unlawful acts: to bring someone to trial on false charges and politically and/or physically purges the person. The champion of the people expels his/her enemies and kills some, otherwise manages to convert surviving enemies into his/her allies. (Plato, 565 e, 566 a).

If no attempt to eliminate the champion were successful, the wicked politician would purge all his/her enemies. (Plato, 566 a-d) The demagogue even starts waging wars in order either to create a new common enemy abroad or even to send his domestic enemies to dangerous battlegrounds. Socrates, it appears to me, is also implying a possible escalation of ‘Imperialism’ as the transition takes place from democracy to tyranny. War needs to be funded by additional tax, thus, causes extra burden on the society, more specifically the people, the taxpayers. The champion, unrestrained without any relevant enemy, now is about to become a tyrant to enslave his/her pupils. (Plato, the Republic, Book VIII: 566 a-567a) Now, the tyrant faces a new challenge: in the absence of material common enemies, new factions emerge among his/her constituents and some of them seek to liberate themselves from their traitor. When some of his/her supporters raise concerns on the chaotic order that the demagogue created, the traitor purge them with the use of violence. (Plato, the Republic, 566 e, 567 a-b) Overall, the tyrant was not only successful in deceiving his constituents with ‘fantasy’ in order to thrive to the top, but now also starts abusing his/her society for his/her own personal interests. Ultimately, the predator hijacks the system and subverts democracy into tyranny. This summarises Socrates’ illustration of the terminal symptom of Democracy. Historical Precedence

Was there any historical precedence to the ominous terminal symptom of democracy that Socrates and Polybius conceived?

In my view, the ancient Rome exhibited a case. In the ancient Rome, the republic was its most democratic achievement: republic (res publica) literally means ‘affair of public’. It was a mixed form of constitution, in which kingship (two annually elected consuls: executive power), aristocratic/oligarchic (the Senate), and democratic (Tribunes and Assemblies) elements co-exist and check and balance one another. Polybius articulated that its institutional check and balance built-in its architecture was conducive to its sustainability. (Polybius, 1979, Book VI) The democratic element in the constitution of the Roman Republic was a Roman way of representative democratic system, but not a direct democracy in the sense of Athenian democracy. Despite its check and balance mechanims that Polybius applauded, the ancient Rome’s most democratic achievement experienced the ominous terminal symptom of democracy in the late republic—specifically from the time of Gracchi Brothers to the assassination of Julius Caesar. It became the battleground of a series of social strifes between the Senate and unscrupulous demagogues—Gracchi Brothers (Tiberius Gracchus c. 169/164 -133 BC; Gaius Gracchus: 154–121 BC)), Catiline (108-62 BC), and Julius Caesar (100-44 BC)—and the republic finally transformed into a form of tyranny, or dynasty, namely the Roman Empire. This historical episode would need another independent reading (Chapter 4) going forward.

|