|

BOND WAVE MAPPING: CASE STUDY 3

Private Debt Cycle Along the Bond Wave Originally published July 23, 2016

Last edited January 2, 2022 by Michio Suginoo This section reviews the private debt cycle along the bond wave.

A detailed definition of the bond wave is described in Secular Rhythm of Bond Wave. Sidney Homer left us a notion that the state of money has something to do with the evolution of the Western civilization. And it extends to a scale of one life cycle of civilization. In studying the bond wave, I intend to apply Homer’s notion in a shorter horizon, say secular time frame. In other word, we can use the bond wave to observe a long-term transformation in the relationship between bond yields and other metrics. My attempt is to capture a notion that the state of money mirrors a broader socio, political, and economic reality. Bond wave mapping provides a heuristic approach to apply historical analogy to make relevant questions about our present and future based on our past. Overview: Secular Rhythm of Private Debt-Money The Global Financial Crisis of 2007/8, emanating from the collapse of the subprime loan bubble in the United States, became an international financial contagion across boarder. And it took place during the most recent bull bond cycle, or the Globalization Wave (the 1980s-today as of 2020) in the Bond Wave term.

The development of the debt-fueled financial crisis in the United States can be viewed in a cyclical framework that is comprised of the following chain of events:

Of course, besides these events, this period was accompanied with other trends—e.g. hollow-out, outsourcing of manufacturing functions to developing economies—amplifying the structural shift of economy. In this chain of events, the role of money was significant. Changes in money supply transformed the structure of real economy. In other words, this period manifested the non-neutrality of money that Hyman Minsky articulated. This reading reviews the non-neutrality of money through private debt cycle along the bond wave. In hindsight, a similar, if not the same, chain of events--the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Central European Banking Crisis of 1931--took place during the previous bull bond cycle, which corresponds to the Vacuum Wave (1920-1945) in terms of the Bond Wave. In other words, both of these two bull bond cycles manifested "private debt cycles": debt-fueled bubble economy and its ensuing destructive systemic financial crises.

Briefly, the two bull bond cycles--the Vacuum Wave and the Globalization Wave--demonstrated two similarities below.

In this section, we project the secular rhythm of private debt activities over the bond wave. More specifically, we apply “bond wave mapping” over four metrics below:

As a reminder, the five bond waves are defined as follows:

These systemic financial crises distinguish themselves from other types of economic distress in the following aspects.

The creation, destruction, and evaporation of modern money

Modern money is primarily created (or destroyed) through two major dynamics: debt creation (repayment) through commercial lending in the private sector; and monetary policy adopted by central banks (McLeay, Radia, & Ryland, 2014, p. 16).

Commercial lending is a private sector’s money creation activity: debt money increases by lending and decreases by repayment, and even evaporates through defaults in the system. More importantly, money is not neutral, since it affects real economy in the long term. According to Hyman P. Minsky (1985), the state of economy shapes the psychologies of economic actors—savers, lenders, and borrowers. Changes in the state of economy can transform their profit expectations (income expectation and expenditure preferences) and liquidity preferences and, ultimately, more diversely their economic behaviours. Then, changes in their behaviours feed back into the state of economy. The period of economic stability bring optimism in the psychologies of these economic actors and induce them to expand the leverage in the system:

Then, it transforms the state of economy from stability to instability in the following order:

Consequential deleveraging becomes destructive to the economic system. If it involves corporate sector, it would compel business to mobilise new innovations to cut labour cost. A dire job expectation destroys consumptions, consequentially, the aggregate demand. It would annihilate the money multiplier in the long run. As Hyman Minsky noted, “stability is destabilising,” and money affects real economic activities: therefore, money is non-neutral. And real economy goes on from one state of disequilibrium to another and ultimately fails to revert to its equilibrium, proving that economic forecasts based on equilibrium are nothing but fallacy. Private debt cycle metricsTo capture the rhythm of the private sector’s debt money (i.e., expansion, destruction, and evaporation) along the bond wave, this readings applies bond wave mapping on the following metrics:

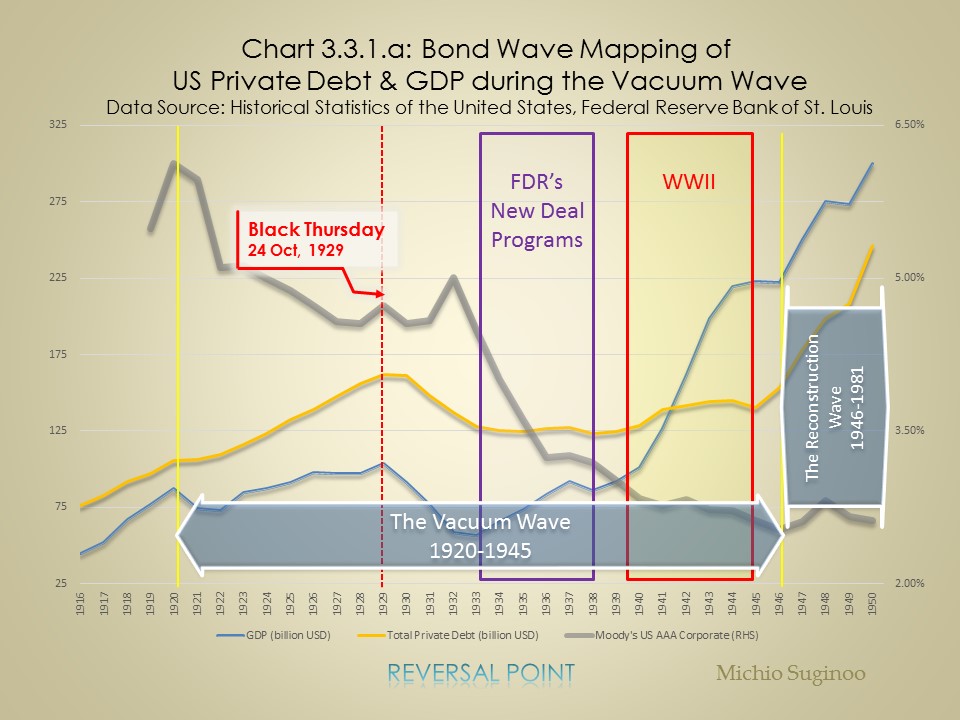

Private Debt Cycle during the Vacuum Wave The following three charts—Chart 3.3.1.a, Chart 3.3.1.b, and Chart 3.3.1.c—cover the period 1916 to 1950 to illustrate the evolution of US private debts around the Great Depression. While the first chart measures the level of private debts and GDP in dollar terms, the second chart traces the relative ratio of private debt to GDP. The third gauges the money multiplier, the driver of credit money creation in the private sector.

In Chart 3.3.1.a:

Total Private Debt to GDP Ratio

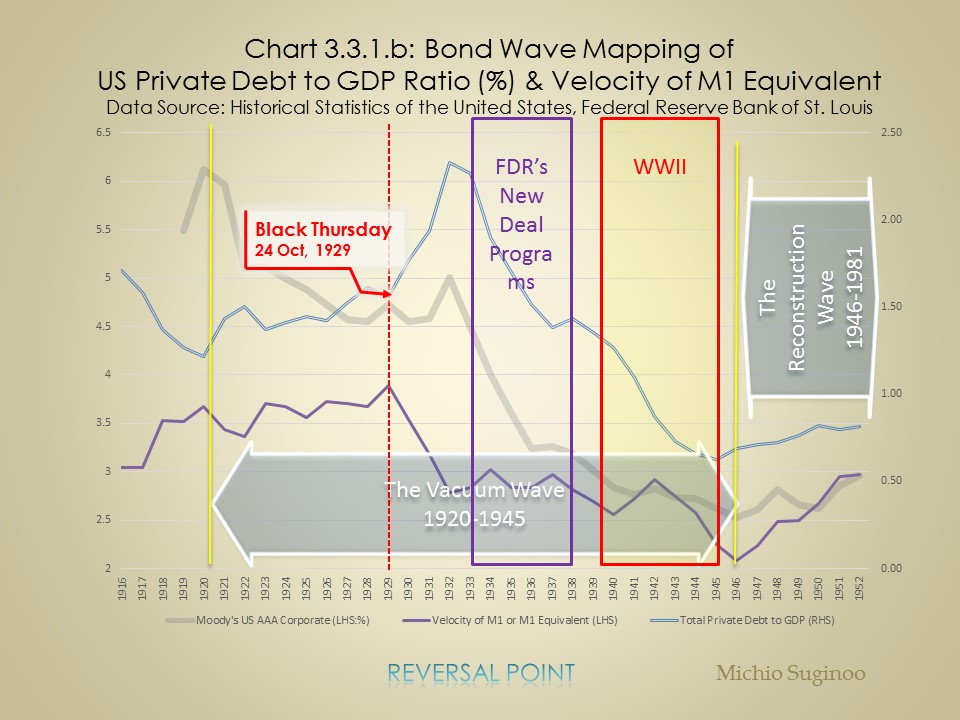

Now we shift our attention to the private debt in relative terms. In Chart 3.3.1.b, "the total private debt-to-GDP ratio" captures one debt cycle along the bull bond market of the Vacuum Wave (the 1920s-1945). The metric measures the proportion of leverage in the system relative to GDP. In 1920, at the start of the bull bond market, it starts expanding from a level around 122% . And it peaks at 233% around the middle of the bull bond market in 1933. Thereafter, it bottoms at 63% in 1945 at the end of the bull bond cycle. This timeline demonstrates a remarkable synchronization between the private debt-to-GDP ratio and the Vacuum Wave. Caution is needed for this interpretation. This notion of synchronization is no more than a synchronization that one private debt cycle (a pair of rising and declining waves) fits into one single bull wave. The peak in the debt-to-GDP ratio lags that of the debt level. During this lag, the ratio continues to increase, it is because the denominator, GDP, declines more drastically than the numerator, debt level, during the period between Black Thursday (1929) and the introduction of the New Deal program (1933). Therefore, the surge in the debt-to-GDP ratio’s (in the absence of a rise in debt level) is a manifestation of the destructive impact of the Great Depression on GDP, economic growth. This destruction is expressed in the rapid decline in the velocity of money in the same chart. How money affects GDP

Velocity of Money

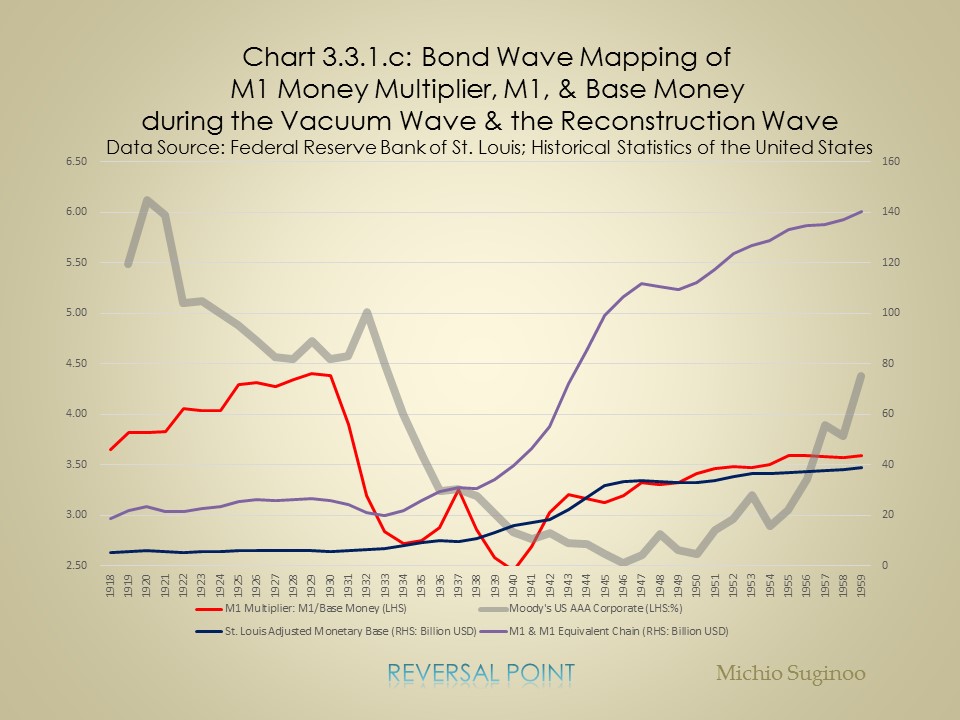

Now, we briefly overview the manifestation of non-neutrality of money—in other words, how money affected GDP—by tracing the velocity of money: GDP divided by M1 or M1 Equivalent. Although the velocity of money might not be considered as a measurement of non-neutrality of money, it illustrates the impact of money on GDP in its trajectory. M1 is a measurement of money in circulation. Since the Federal Reserve Bank did not release M1 statistics before 1959, for the period prior to 1959 we must employ a proxy for M1 to construct the chart approximating the velocity of M1 money stock: Friedman & Schwartz’s M1 series before 1946; Rasche’s M1 series for 1947 to 1958. (Carter et al., 2006, pp. Vol 3: 604-607) We call these proxies collectively “M1 Equivalent” for our discussion purposes. We measure the velocity by dividing GDP by M1 Equivalent. Chart 3.3.1.b illustrates the trajectory of the velocity of M1 Equivalent from 1916 to 1952. The velocity measure, after increasing from 3.04 to 3.67 during the period 1916 to 1920, remains high, with the exception of a dip from 1921 to 1922, peaking at 3.89 in 1929, the year of the Wall Street Crash. Thereafter, it reverses direction downward to the end of WWII, although it demonstrates some stability during the New Deal era and some rebound in the mid–WWII period. In brief, until the beginning of the succeeding bear bond cycle, the Reconstruction Wave (1946-1981), the velocity of money fails to demonstrate a sustainable recovery. In principle, the velocity of money collapses significantly throughout the post-crisis period—from the Wall Street Crash in 1929 until the end of WWII (1945). This illustrates how the post-crisis deleveraging process diminished the velocity of money. Overall, the large-scale fiscal expansion of the New Deal and the WWII special war demand did not reverse the post-crisis collapse in the velocity of money. It took another massive fiscal expansion, the post-war reconstruction effort, to restore the velocity of money: it required a series of unconventional fiscal expansions and possibly the destruction of war. Here as well, the rhythm in non-neutrality of money and the bond wave demonstrate a remarkable synchronization. Money Multiplier Finally, Chart 3.3.1.c demonstrates “bond wave mapping” over the historical chart of money multiplier. The M1 money multiplier—M1 or M1 equivalent divided by the money base—gauges the transmission effectiveness of monetary base into money supply. Thus, it measures the private sector’s ability to create credit money. Although monetary authorities can closely influence the monetary base, they can only loosely induce money multiplier to modulate money supply. Money multiplier measures the private sector’s ability to create credit money through commercial lending: this mechanism drives the circulation of money in the private sector. As a matter of fact, this chart illustrates how indirect and uncertain monetary authority’s influence over the circulation of money could be. In 1929, the year of the Wall Street Crash, the money multiplier (M1 multiplier in the chart) reached its high at 4.4, then continued to remain relatively stable for one year, thereafter plunged toward 2.72 until1934. Along with the progression of the New Deal program, it made a transient recovery until 1937 to 3.25, then collapsed again until the year before the US participation in WWII. This suggests that, while the New Deal boosted the money multiplier for a short term, it was only transient and did not fully restore its sustainable mechanism. It took WWII—another massive fiscal expansion and the destruction of war—for the money multiplier to restore itself.

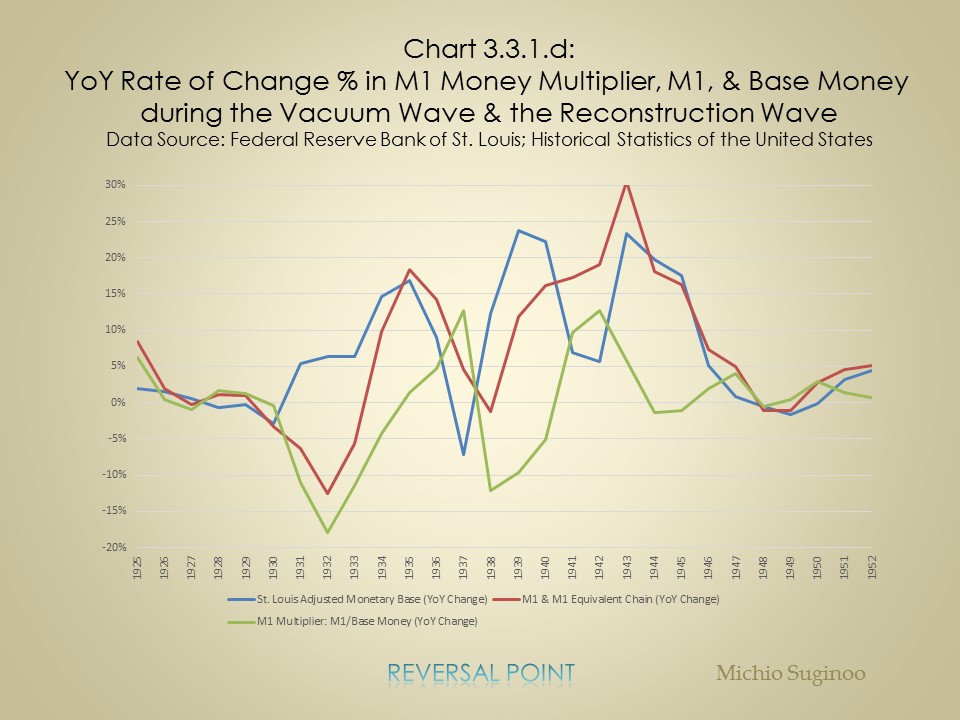

Now, in order to take a closer look at the interaction between the monetary base and M1 equivalent (money supply), Chart 3.3.1.d tracks year-over-year (YoY) change in both monetary base and M1. Overall, this chart reveals that the change in M1 equivalent (money supply) tends to lag the change in the monetary base. It is quite intuitive. The one-year stability observed earlier in the money multiplier from 1929 to 1930 is because both metrics, M1 and the money base, declined moderately at comparable rates. Then, despite an increase in the YoY rate of change in monetary base up to 6% from 1930 to 1932, the YoY change in M1 made a remarkable decline. It required an even stronger rate of increase in the monetary base—from 6.4% to 18.4% from 1933 to 1935 to boost the YoY change in M1 money. The recovery in money supply (M1 equivalent) coincided with the early stage of FDR’s administration and the introduction of the New Deal programs (fiscal expansion).

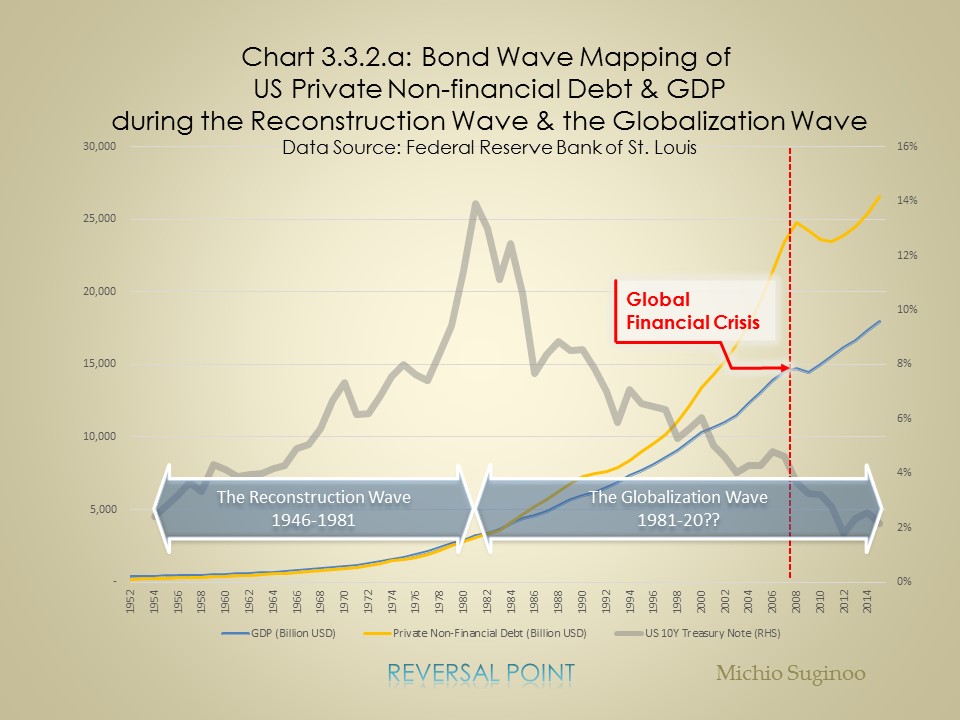

Thereafter, for the rest of the New Deal era, the YoY rate of change in the monetary base again plunged from its peak of 18.4% in 1935 to –7.2% in 1937. Accordingly, M1 demonstrated a drop in its YoY rate of change. This implies that the absence of an increase in the monetary base might be associated with the plunge in M1 in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Then, WWII reversed the course of events. From its onset, the YoY rate of change in M1 increased to 30.5% in 1943, lagging behind the drastic increase in monetary base that has taken place since 1938. Thereafter, despite a drop in its level, the YoY rate of change in M1 remains above the zero line, with a minor breach from 1948 to 49. This illustrates the background behind the remarkable recovery in the money multiplier after 1940. So far, we have observed one historical debt-cycle case within a bond bull cycle of the Vacuum Wave (1920-1945). Next, we move to another case in the Globalization Wave (the 1980s-today as of 2020). Private Debt Cycle During the Reconstruction and Globalization Waves Chart 3.3.2.a tracks the level of private non-financial debt and GDP during two bond waves—the Reconstruction Wave (1946-1980) and the Globalization Wave (1981-today as of 2020). The private non-financial debt level and GDP rose gradually at roughly the same rates during the Reconstruction Wave (1946-1980). Entering the Globalization Wave (1981-today as of 2020), the private non-financial debt level accelerated faster than the GDP and made its near-term peak at USD 24,741 billion in 2008 at the onset of the Global Financial Crisis. However, in contrast to the case of the Great Depression, it did not collapse afterwards. Instead, after a temporary setback, it kept rising. From this dollar term chart, the debt level does not form one cycle—a series of a rising and an ensuing declining trends—in contrast to the case of the Great Depression.

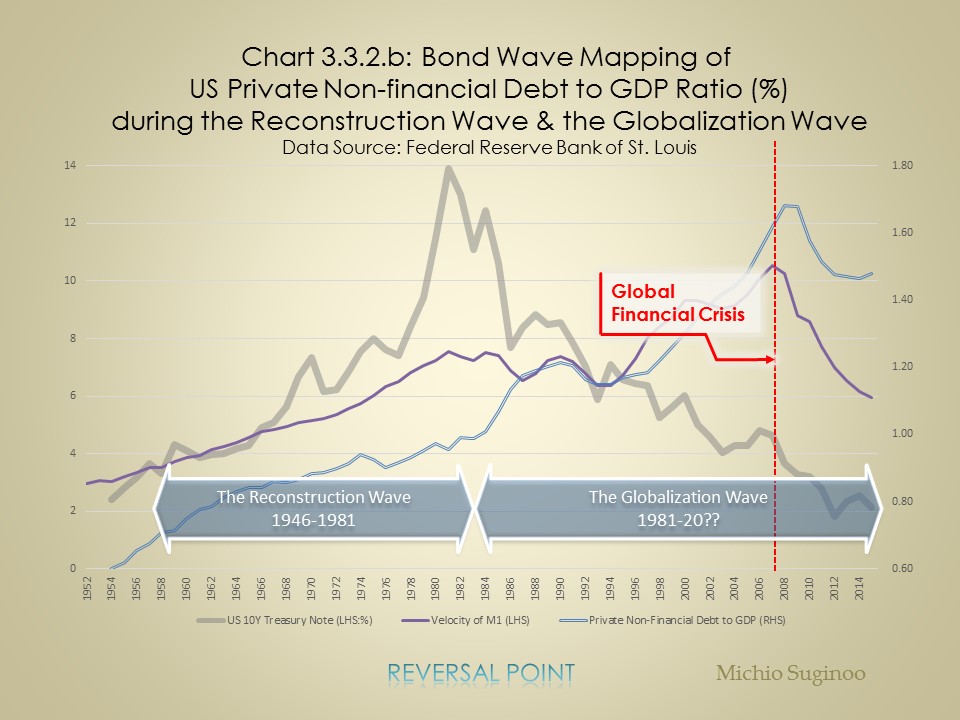

Chart 3.3.2.b measures US private non-financial debts in relative to GDP, showing its debt to GDP ratio. The ratio demonstrates a declining trend during the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (Chart 3.3.2.b). In 2008, the ratio peaked at 1.68, then declined notably for some time toward 1.46 until 2014 before stabilizing briefly.

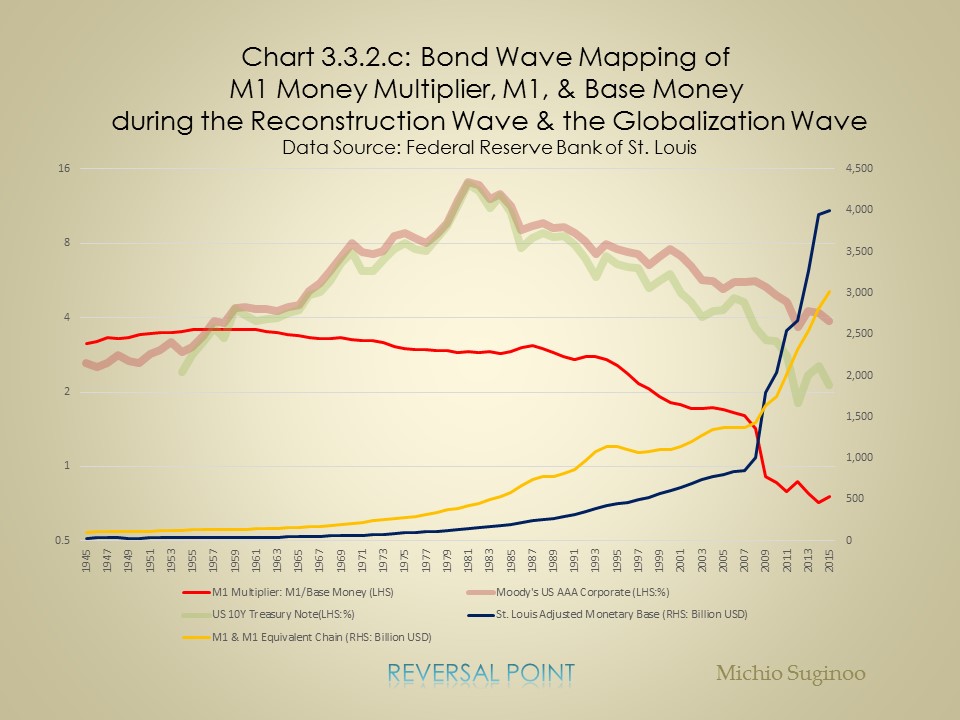

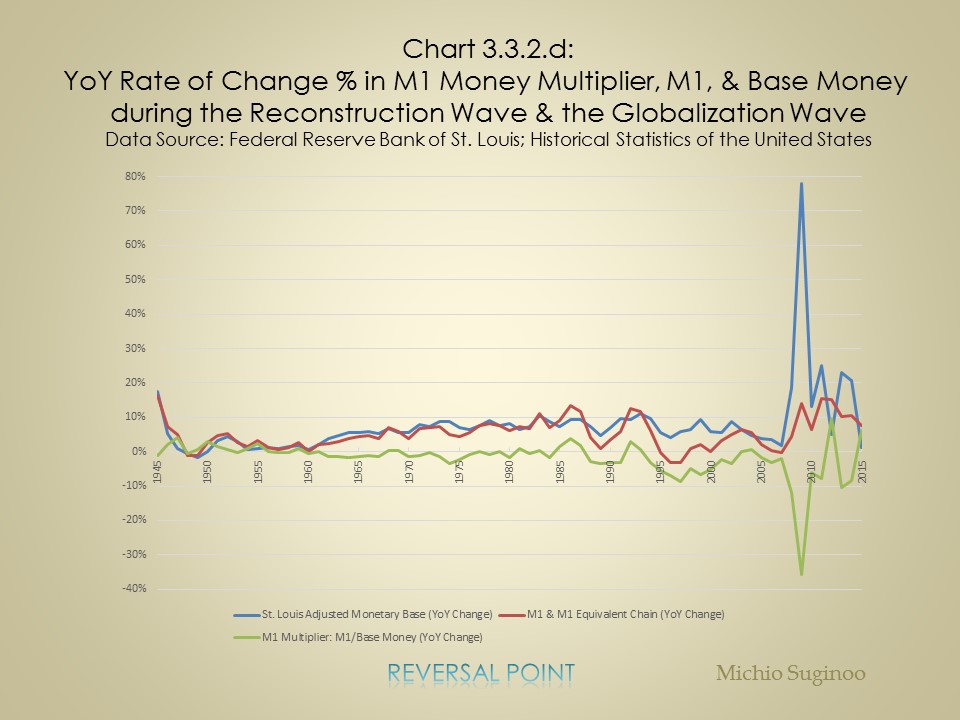

Now when we trace the velocity of money, the impact of money on GDP, the presence of one cycle appear more clearly. In terms of the velocity of M1, it peaked at the outset of the crisis and collapsed toward the end of the Vacuum Wave. The velocity of money demonstrates analogy with the Great Depression case. Now we turn to the money multiplier for this period in Chart 3.3.2.c. Like the previous case of the Great Depression, the money multiplier plunged rapidly after the outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007. Its level collapsed from 1.61 in 2007 to the historical low of 0.71 in 2014.

Nevertheless, a salient contrast can be seen in the trajectories of monetary base between the Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis (dark blue lines in Chart 3.3.1.c and Chart 3.3.2.c, respectively). In the former case, the monetary base did decline in the aftermath of the crisis; in the latter case, it made a historic surge thanks to unprecedent quantitative easing (QE). Despite the historic boost in monetary base by monetary authority, money multiplier collapsed. This shows us that the increase in the monetary base was not effective in restoring the private sector’s ability to drive the circulation of money. It also suggests that the historic expansion in liquidity supported the persistence in the level of private non-financial debt after the crisis (Chart 3.3.3.a). A natural ensuing process of deleveraging, an automatic adjustment mechanism to liquidate excess leverage in the aftermath of the systemic financial bubble, might have been paralyzed by the liquidity expansion. On the other hand, it failed to boost money multiplier. This suggests the lack of demand. This is a reflection of policy failures in restoring a primary driver of economy, income expectation and employment. This implies the need for a demand side measure. Since quantitative easing (QE) allowed the monetary authority to purchase private securities directly, the QE process does not necessarily involve an adjustment of monetary base in its passage. The monetary authority, through its direct purchase in private securities, has impaired the auto-correcting demand-supply mechanism—or the price discovery mechanism, if you like—of the market, and may have failed to allow the money multiplier mechanism (the private sector’s economic driver) to be overhauled.

Resemblances and Differences in Two Private Debt Cycles These “bond wave mappings” revealed recurrences and evolution of the debt cycle by expressing resemblances and differences in these two systemic financial crises: the Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis. Here is a brief recap of the recurrences (or resemblances) and evolutions (differences) in the debt cycle over the bond wave.

Resemblances: Recurrent Features

Together with our observation of two immediate negative impacts of the systemic financial crises on GDP, we can confirm the long-term impact of money on real economy.

|