|

THE SECULAR RHYTHM OF THE BOND WAVE: Secular Macro Behavioural Dynamics of Political Economy- Its Indisputable Uncertainty and Irregularity & Equally Undeniable Pendulum Recurrent Dynamics Originally published July 23, 2016

Last edited June 15, 2017 By Michio Suginoo In the chapter of “Supra-Secular Rhythm: Sidney Homer's Saucer,” we had a glimpse of the supra-secular rhythms of interest rates by tracing Homer’s Saucer, the centennial best credit frontier. Homer’s implication was that the state of money might have something to do with the evolution of western civilization. The time horizon of the supra-secular rhythm was too long to associate it with our lifetime experience.

This section will scale down the time horizon to a secular cycle level and come one step closer to our lifetime horizon. The purpose of this attempt is to question the relevance of Homer’s notion in a secular scale. In other words, it is to see whether the state of money has something to do with secular transformations in broader socio, political, economic reality in the western world. In doing so, this section gauges secular[1] rhythm by tracing long-term interest rates or bond yields since the 19th century, focusing on two powerhouses of the world economy—the United Kingdom from the turn of the 19th century to the mid-20th century, and the United States from 1920 to today. Peripheries’ socio-political-economic affairs are beyond the scope of this attempt. The rationale for selecting long- versus short-term interest rates is the latter’s sensitivity to short-term fluctuations in the state of the economy in our modern times. Highly volatile data are susceptible to temporal over-shootings, and lack quality as a proxy for the state of credit [2]. By tracing long-term interest rates, we can better gauge a secular implication of interest rates. We’ll call their trajectory the “bond wave.” From here on, we will use “the secular rhythm of long-term interest rates” and “bond wave” as interchangeable terms.

|

|

Milestone events that marked paradigm shifts in the currency regimes of major economies unfolded within both extreme ranges, top and bottom, of the bond wave. This empirical evidence suggests that an environment within the extreme ranges of bond yields seems to intensify the potential for paradigm shifts in the currency system.

Currently, we are positioning (presumably) near bottom of the bond wave in terms of yield level. In keeping with the empirical evidence, we may be compelled to ask a legitimate question whether we are about to encounter another paradigm transformation in the currency system. |

2) Evolution in Price and Inflation Cycle:

|

In relation to price cycles, the bond wave showed drastic behavioural changes somewhere between the 1970s and 1980s. Prior to the 1970s, the bond wave had demonstrated remarkable synchronization with the price level, as observed in Gibson’s Paradox, for more than two and a half centuries; after the 1980s, it started exhibiting a new behaviour, synchronizing with the retrospective inflation experience, measured as the trailing average of inflation rates (as illustrated by Professor Robert Shiller). The change in behaviour of the bond wave indicates some structural changes during the post-WWII period, which coincides with the gradual introduction of the floating currency exchange rate system—from the Bretton Woods System (1944) to Nixon Shock (1971).

In addition, the behaviour of deflation changed as the paradigm shifts in the currency regime took place. The bond wave mapping captures the transformations in these two dynamisms—the behaviour of deflation and the paradigm shift in currency regime. It captures the differences in price behaviour between two regimes—the fixed exchange rate regime under the metallic system and the floating exchange rate regime under fiat money. |

3) Private Debt Cycle:

|

The recent two bull bond waves (one from 1920 to 1946; the other from 1982 to now) exhibited remarkable synchronization with the secular rhythm in the private sector’s debt cycle. Two historical systemic financial crises—the Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis—unfolded in the middle of bull bond waves after a previous prolonged period of economic stability; thereafter, debt deflation unfolded and exerted persistent deflationary pressure that led to protracted economic stagnation.

This secular rhythm in the private sector’s debt cycle is a manifestation of the non-neutrality of the private sector’s modern money—debt money created through commercial lending. Accordingly, the two recent bull bond waves captured transformations in the non-neutrality of modern debt-money. |

4) Government Intervention Cycle and Debt Magic (Negative Real Interest Rates) Cycle:

|

The sovereign debt cycle transformed drastically after the Great Depression. This transformation is captured by the bond wave: the spike in sovereign debt shifted from the top range to the bottom range of the bond wave at the New Deal policy. While prior to the Great Depression, a massive sovereign debt issuance was motivated primarily by war funding, thereafter it became dictated by economic motives to counteract economic distress caused by the private sector’s earlier systemic financial crisis. As its backdrop, the suffrage movement gradually progressed and served as a cornerstone of the transformation in political decision-making.

The rhythm of the Debt Magic, technical debt reduction or financial repression, which is conjured by negative real yields, synchronizes with inflationary national contingencies, such as wars. While inflationary contingencies called for negative real yields to counteract negative economic consequences, deflationary contingencies trapped real yields in the positive territory, and caused protracted economic stagnation. The Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis demonstrated cases for the latter, where the Debt Magic cannot be conjured effectively. The bond wave mapping identifies those two deflationary cases in analogous locations in the bond wave. The empirical case during the aftermath of the Great Depression might provide us with a heuristic analogy to our present and future. |

A Bayesian approach: incorporating new information

Naturally, we cannot simply project our past experiences into the present and the future. The bond wave must not be interpreted deterministically; rather, it should be interpreted probabilistically. In a way, this requires a Bayesian approach; that is, we need to incorporate new developments into our probabilistic application of the bond wave.

I presume a hypothetical notion that the bond wave is a manifestation of secular rhythms in the macro-level product of political economic collective behaviours. Material events that alter such secular macro political-economic behaviours can transform the bond wave. Therefore, the bond wave shall not be considered as the causal determinant of our macro-secular behaviour. Nevertheless, it does seem to express certain constraints or conditions that our past has built up hitherto. Therefore, in a way, there seem to exist “feed-in, feed-back” interactions between the bond wave and our secular macro-political-economic behaviour.

The rest of this chapter outlines the secular rhythm of bond yields themselves. This process is a prerequisite to building any further framework of Bond Wave.

I presume a hypothetical notion that the bond wave is a manifestation of secular rhythms in the macro-level product of political economic collective behaviours. Material events that alter such secular macro political-economic behaviours can transform the bond wave. Therefore, the bond wave shall not be considered as the causal determinant of our macro-secular behaviour. Nevertheless, it does seem to express certain constraints or conditions that our past has built up hitherto. Therefore, in a way, there seem to exist “feed-in, feed-back” interactions between the bond wave and our secular macro-political-economic behaviour.

The rest of this chapter outlines the secular rhythm of bond yields themselves. This process is a prerequisite to building any further framework of Bond Wave.

Irregularity of the Bond Wave

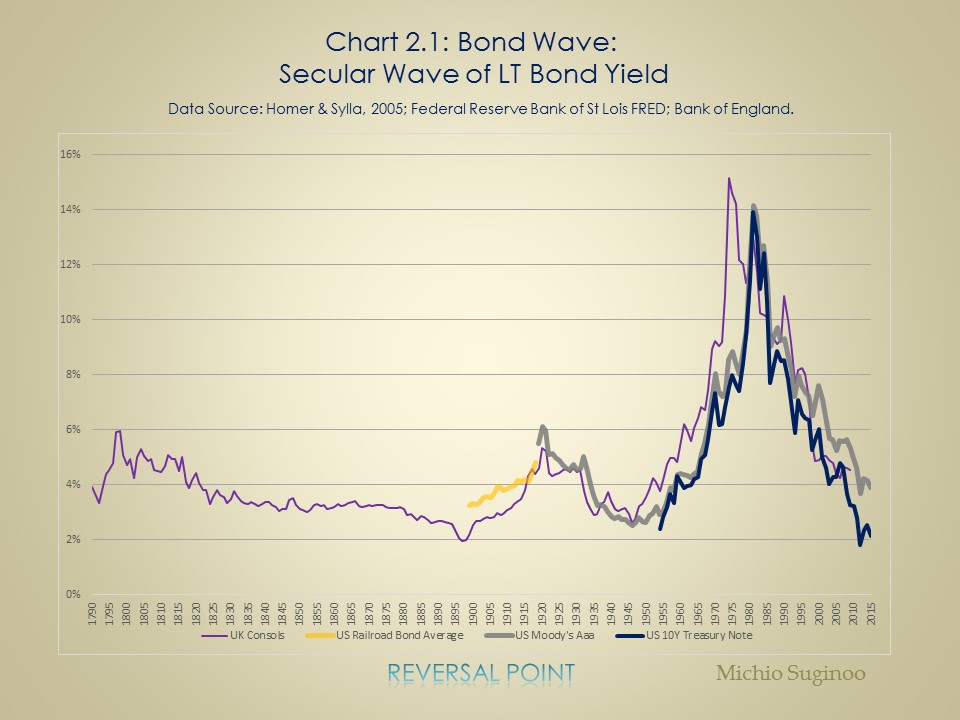

Chart 2.1 traces three proxy benchmarks of long-term bond yields in the United Kingdom and the United States, the global economy’s centres of gravity since the 19th century:

- UK Consols since the 19th century;

- US prime corporate bonds since the turn of the 20th century; and

- US 10-year treasury notes since 1954.

Here, our primary subject is the nominal yields of default-risk-free securities in principle: therefore, government bonds issued by the United Kingdom during the 19th century and first quarter of the 20th century, and the United States from then until today. These government bonds can be deemed to be default risk-free assets in nominal term[3] for the majority of each corresponding period[4]. In terms of benchmarks, our focus is on UK Consols and US 10-year treasury note.

About the UK Consols data, Brian R. Mitchell (1988) wrote: “The yield on (the UK) Consols from their inception to the present day (…) constitutes one of the longest unbroken and consistent series” among historical statistics available today (Mitchell, 1988, p. 649).

About the UK Consols data, Brian R. Mitchell (1988) wrote: “The yield on (the UK) Consols from their inception to the present day (…) constitutes one of the longest unbroken and consistent series” among historical statistics available today (Mitchell, 1988, p. 649).

The belated debut of the US 10-year treasury note

In the case of the younger counterpart, the United States, such a long unbroken and consistent series is a rare thing. The US 10-year treasury note only dates to April 1953. To begin with, until the New Deal’s historic fiscal expansion in the aftermath of the Great Depression, the US federal government had not issued substantially sized bonds except for war funding purposes[5]. It took some decades, with an interruption by WWII, for the 10-year treasury note to make its debut.

In this context, prime corporate bonds fill the gap by acting as a supplemental coherent proxy, with a minor margin, tracing further back to the past. For simplicity as well as practical purposes, for the period prior to the debut of the US 10-year treasury note, we refer to the US prime corporate bond period as a secondary proxy for the United States to capture the trajectory of bond yields in continuity.

In this context, prime corporate bonds fill the gap by acting as a supplemental coherent proxy, with a minor margin, tracing further back to the past. For simplicity as well as practical purposes, for the period prior to the debut of the US 10-year treasury note, we refer to the US prime corporate bond period as a secondary proxy for the United States to capture the trajectory of bond yields in continuity.

Some historical perspective

In the historical perspective of interest rates, dating to Babylonian times, default risk-free sovereign security is a recent concept. In antiquity, loans to absolute monarchies were not safe transactions. Monarchs could execute lenders at their convenience if they had trouble repaying a debt. Sovereign securities should, therefore, be classified as far from risk-free. If we focus on post–Dark Age Western history, the Glorious Revolution in 1688–89—when the UK adopted a constitutional monarchy, and started placing limits on its monarch’s spending discretion—should probably be considered one of the milestone events that sparked prudence and credibility in the sovereign bond world.

Anatomy of the bond wave: bull and bear waves

Returning to Chart 2.1: For the entire period, the most salient feature is poor regularities in the secular rhythm of bond yields. To acknowledge this salient feature, we can call this rhythm a “wave” to distinguish it from a conceptualized series of regular cycles.

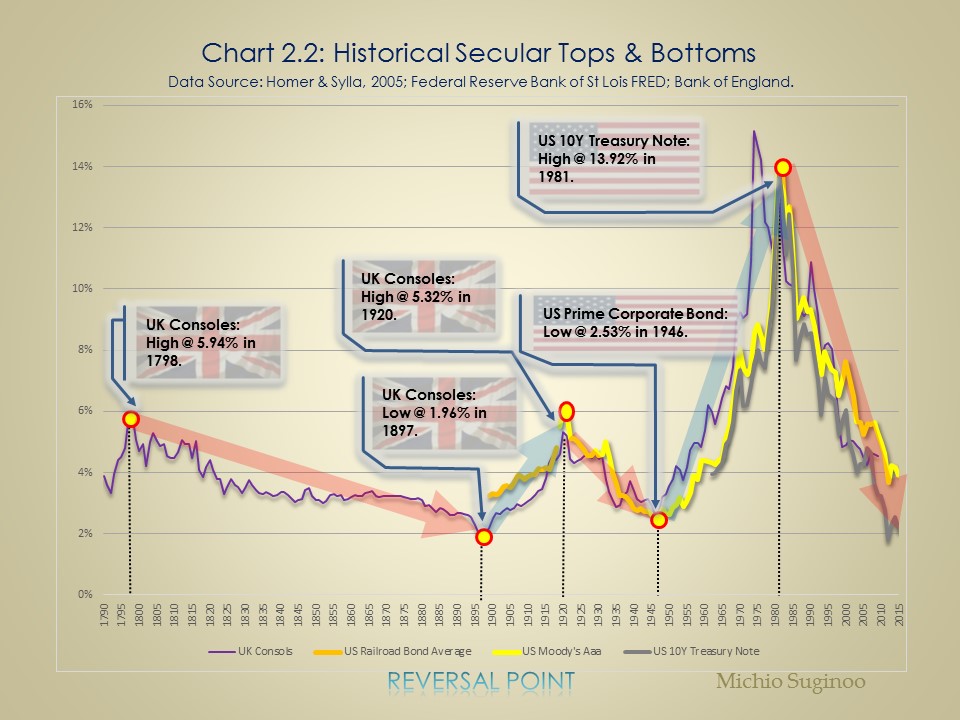

For our discussion purposes, in Chart 2.2, let us divide the historical bond wave into parts—its secular bull periods and secular bear periods—by separating it at secular highs and secular bottoms. “Bull” and “bear” here follow the conventional jargon of the investment world: bull refers to rising prices; bear, to falling prices.

For our discussion purposes, in Chart 2.2, let us divide the historical bond wave into parts—its secular bull periods and secular bear periods—by separating it at secular highs and secular bottoms. “Bull” and “bear” here follow the conventional jargon of the investment world: bull refers to rising prices; bear, to falling prices.

Bond yield/price primer

As a reminder to general readers, bond yields and prices have an inverse relationship. An ascending wave, taking off at a secular bottom toward its succeeding closest secular high in terms of bond yields, is a manifestation of a secular bear market in terms of bond prices: rising bond yields translate into falling bond prices and, therefore, a secular bear trend. On the other hand, a descending wave, emerging from a secular high to its closest succeeding secular bottom in terms of bond yields, is a manifestation of a secular bull trend: falling bond yields translate into rising bond prices and, therefore, a secular bull trend.

Below, when referring to the entire system or dynamism of the rhythm of the bond yields, we refer to it in singular as “the bond wave”; when we refer to its components collectively—bull waves and bear waves—we call them “bond waves.”

Below, when referring to the entire system or dynamism of the rhythm of the bond yields, we refer to it in singular as “the bond wave”; when we refer to its components collectively—bull waves and bear waves—we call them “bond waves.”

Bull and Bear Bond Waves since the 19th Century

Chart 2.2 projects the determination of the secular bull and bear of the bond wave following the approach described above. We will review the characteristics of each bond wave below.

Along the UK Consols yields, we can define the first three secular waves:

As a reminder regarding US bond yields, we refer to the prime corporate bond up to the debut of the 10-year treasury note. For that reason, here we use the US prime corporate bond to capture the fourth wave.

We can confirm the fourth bond wave along the US prime corporate bond yields from the wave’s bottom at 2.53% in 1946 to its top at 14.17% in 1981 in the form of a secular bear wave (rising yield: falling price) in the total yield gap of an 11.64%. Thereafter, we switch our benchmark to the US 10-year treasury note to identify the fifth wave. US 10-year treasury note yields decline from their high of 13.92% in 1981 to the realm of 2% today; this bull wave (declining yield: rising price) is tentatively around 12%.

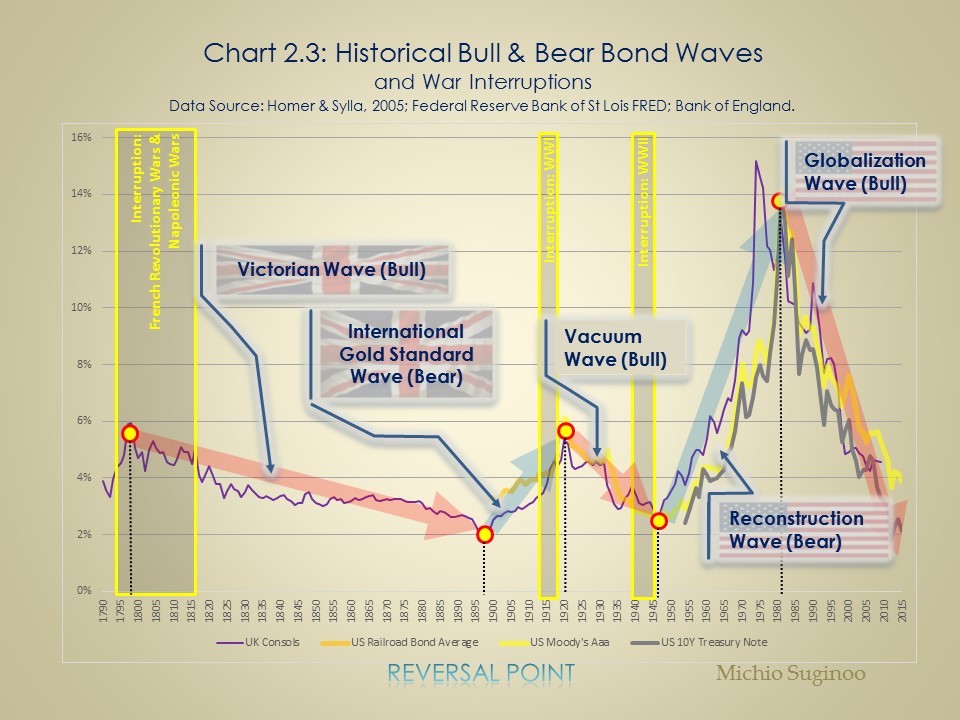

In order to acknowledge the extraordinary impacts of large-scale wars, in Chart 2.3 we shade the periods of hegemonic wars that directly involved the homelands of the centres of gravity in the world economic and political system:

- The first bond wave can be identified from its first secular high at 5.94% in 1798 to its first low at 1.96% in 1897 in the form of a secular bull wave (declining yield: rising price) in the total yield gap of a 3.98%.

- From then until the second high at 5.32% in 1920, the second bond wave can be identified in the form of a secular bear wave (rising yield: falling price) in the total yield gap of a 3.36%.

- Then, the third bond wave follows and continues until its second low at 2.60% in 1946 in the form of a secular bull wave (declining yield: rising price: bull) in the total yield gap of a 2.72%.

As a reminder regarding US bond yields, we refer to the prime corporate bond up to the debut of the 10-year treasury note. For that reason, here we use the US prime corporate bond to capture the fourth wave.

We can confirm the fourth bond wave along the US prime corporate bond yields from the wave’s bottom at 2.53% in 1946 to its top at 14.17% in 1981 in the form of a secular bear wave (rising yield: falling price) in the total yield gap of an 11.64%. Thereafter, we switch our benchmark to the US 10-year treasury note to identify the fifth wave. US 10-year treasury note yields decline from their high of 13.92% in 1981 to the realm of 2% today; this bull wave (declining yield: rising price) is tentatively around 12%.

In order to acknowledge the extraordinary impacts of large-scale wars, in Chart 2.3 we shade the periods of hegemonic wars that directly involved the homelands of the centres of gravity in the world economic and political system:

- from the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1793 to the end of Napoleonic War in 1817;

- the period of WWI from its outbreak in 1914 to its conclusion with the Versailles Treaty in 1919; and

- the period of WWII from its outbreak in 1939 to its end in 1945.

5 Bond Waves Since the 19th Century:

The Victorian Wave (1789-1897)

The International Gold Standard Wave (1897-1920)

The Vacuum Wave (1920-1946)

The Reconstruction Wave (1946-1982)

The Globalization Wave (1982-n.d.)

The International Gold Standard Wave (1897-1920)

The Vacuum Wave (1920-1946)

The Reconstruction Wave (1946-1982)

The Globalization Wave (1982-n.d.)

While acknowledging the extraordinary periods of these hegemonic wars, we can name each secular wave based on its peace-time characteristics as below. Chart 2.3. reflects those named on Chart 2.2.

- Victorian Wave—the bull wave between 1798 and 1897 named after the Queen Victoria, because most of its peaceful period coincides with her life (1819 to 1901: reigned between 1837 and 1901): including war times, the 99-year secular bull wave in the total yield gap of a 3.98% decline in UK Consols yields, ranging from 5.94% in 1798 to 1.96% in 1897.

- International Gold Standard Wave—the bear wave named after the international monetary regime during the peacetime of the period: including WWI, the 23-year secular bear wave in the total yield gap of a 3.36% increase in UK Consols yields, ranging from 1.96% in 1897 to 5.32% in 1920.

- Vacuum Wave—the bull wave named after the power vacuum to describe the state of international political affairs during the inter-war periods in post–WWI Western Europe: including WWII at arrear, the 2-year bull wave in the total yield gap of a 2.72% decline in UK Consols yields, ranging from 5.32% in 1920 to at 2.60% in 1946.

- Reconstruction Wave—the post-WWII bear wave named after the Reconstruction Era to describe the state of international political affair: the 40-year secular bear wave in the total yield gap of an 11.64% increase in the yields of US prime corporate bonds, ranging from 2.53% in 1946 to 14.17% in 1981.

- Globalization Wave—from 13.92% in 1982 to 2.14% in 2015, and still on its way as of June 2016: so named to reflect the extension of global trade and commercial prosperity from advanced economies to peripheries during this period; the more than 34-year secular bond bull wave in the total yield gap of an approximately 12% (tentative) decline in US 10-year treasury note yields. It records the historical low. However, US prime corporate bond yields have not reached the previous low yet, suggesting the potential for further decline. Therefore, this wave might form a much longer floor in terms of the US 10-year treasury note.

A closer look at bond wave irregularities

Repeatedly, the most salient feature of the secular bond wave is its irregularities in shape: both in magnitude and in duration. Visually, the series of these waves does not appear to demonstrate any predictive power. Now as our first attempt, let us acknowledge the irregularities one by one for each wave.

The first secular bond wave, the Victorian Wave (bull), manifested the longest and most gradual progression among all. It started with two hegemonic wars and took 99 years to wind down, with a medium magnitude of a 3.98% secular decline in UK Consols’ yields for the entire period. The secular decline in yields indicates an advancement in credit activities.

The succeeding two secular waves—the International Gold Standard Wave and the Vacuum Wave—also accompany hegemonic wars, WWI and WWII respectively. These two waves are much more compact in their time horizons when compared with their preceding peer, the Victorian Wave.

Then the most recent pair—the Reconstruction Wave and the Globalization Wave—exert a much larger swing with rigor, when compared with the preceding pair, suggesting that some underlying structural transformation might have taken place between the two pairs.

The Reconstruction Wave produced an 11.64% yield increase in its magnitude and endured 35 years in terms of its time horizon. In comparison with its preceding bear peer, the International Gold Standard Wave, its size is amplified approximately 3.5 times in its yield scale and 1.7 times in its duration.

The Globalization Wave also made a large swing comparable with its preceding wave, the Reconstruction Wave. Although it has not completed its wave yet, its yield advance is 11.78% and its duration was more than 34 years as of 2015. In comparison with its preceding bull peer, the Vacuum Wave, its yield advance was roughly about 4.4 times and its duration approaching 1.3 times, as of 2015.

The first secular bond wave, the Victorian Wave (bull), manifested the longest and most gradual progression among all. It started with two hegemonic wars and took 99 years to wind down, with a medium magnitude of a 3.98% secular decline in UK Consols’ yields for the entire period. The secular decline in yields indicates an advancement in credit activities.

The succeeding two secular waves—the International Gold Standard Wave and the Vacuum Wave—also accompany hegemonic wars, WWI and WWII respectively. These two waves are much more compact in their time horizons when compared with their preceding peer, the Victorian Wave.

Then the most recent pair—the Reconstruction Wave and the Globalization Wave—exert a much larger swing with rigor, when compared with the preceding pair, suggesting that some underlying structural transformation might have taken place between the two pairs.

The Reconstruction Wave produced an 11.64% yield increase in its magnitude and endured 35 years in terms of its time horizon. In comparison with its preceding bear peer, the International Gold Standard Wave, its size is amplified approximately 3.5 times in its yield scale and 1.7 times in its duration.

The Globalization Wave also made a large swing comparable with its preceding wave, the Reconstruction Wave. Although it has not completed its wave yet, its yield advance is 11.78% and its duration was more than 34 years as of 2015. In comparison with its preceding bull peer, the Vacuum Wave, its yield advance was roughly about 4.4 times and its duration approaching 1.3 times, as of 2015.

Secular bond wave's irregularities

The notable behavioural irregularities among those five secular bond waves across time can be summarised as follows:

On the other hand, the secular bond waves’ trajectories suggest that it is not a completely random event or perfect chaos. Despite the indisputable presence of irregularities, pendulum-like alterations between the secular bull wave and secular bear wave are present. Within each wave unit, which is defined between its high and low ends, a secular quality in either bear or bull is consistently maintained with some short-term deviations.

There is a compelling hint of some systematic underlying mechanism in maintaining those persistent qualities within each wave to keep driving a pendulum swing. If that is the case, what would be the systematic underlying mechanism to drive alterations between bull and bear waves? It is a legitimate question.

- a long gradual progression in the Victorian Wave;

- a successive pair of compact waves observed in the International Gold Standard Wave and the Vacuum Wave; and

- a larger swing, in comparison with the preceding pair, observed in the pair of the Reconstruction Wave and the Globalization Wave.

On the other hand, the secular bond waves’ trajectories suggest that it is not a completely random event or perfect chaos. Despite the indisputable presence of irregularities, pendulum-like alterations between the secular bull wave and secular bear wave are present. Within each wave unit, which is defined between its high and low ends, a secular quality in either bear or bull is consistently maintained with some short-term deviations.

There is a compelling hint of some systematic underlying mechanism in maintaining those persistent qualities within each wave to keep driving a pendulum swing. If that is the case, what would be the systematic underlying mechanism to drive alterations between bull and bear waves? It is a legitimate question.

The notable behavioural irregularities among those five secular bond waves across time can be summarised as follows:

On the other hand, the secular bond waves’ trajectories suggest that it is not a completely random event or perfect chaos. Despite the indisputable presence of irregularities, pendulum-like alterations between the secular bull wave and secular bear wave are present. Within each wave unit, which is defined between its high and low ends, a secular quality in either bear or bull is consistently maintained with some short-term deviations.

There is a compelling hint of some systematic underlying mechanism in maintaining those persistent qualities within each wave to keep driving a pendulum swing. If that is the case, what would be the systematic underlying mechanism to drive alterations between bull and bear waves? It is a legitimate question.

- a long gradual progression in the Victorian Wave;

- a successive pair of compact waves observed in the International Gold Standard Wave and the Vacuum Wave; and

- a larger swing, in comparison with the preceding pair, observed in the pair of the Reconstruction Wave and the Globalization Wave.

On the other hand, the secular bond waves’ trajectories suggest that it is not a completely random event or perfect chaos. Despite the indisputable presence of irregularities, pendulum-like alterations between the secular bull wave and secular bear wave are present. Within each wave unit, which is defined between its high and low ends, a secular quality in either bear or bull is consistently maintained with some short-term deviations.

There is a compelling hint of some systematic underlying mechanism in maintaining those persistent qualities within each wave to keep driving a pendulum swing. If that is the case, what would be the systematic underlying mechanism to drive alterations between bull and bear waves? It is a legitimate question.

Central Questions

Ideally, we need to be able to distinguish between these two forces: indisputable irregularities, potentially as a manifestation of evolutions; and undeniable, persistent, pendulum-like forces, potentially as a manifestation of recurrences:

Overall, the irregularity of the bond wave makes it appear impossible for us to make any empirical inferences about it. On the surface, it does not seem to have any analytical use. Very discouraging! Should we just pretend it didn’t exist?

- What caused such notable irregularities in the behaviours among those five secular bond waves across time?

- What altered their behaviours in magnitude and in period?

- Is there any systematic driving force underlying the bond wave? Or is it perfect chaos that drives the wave?

Overall, the irregularity of the bond wave makes it appear impossible for us to make any empirical inferences about it. On the surface, it does not seem to have any analytical use. Very discouraging! Should we just pretend it didn’t exist?

Some notable examples

The past five bond waves seem to reflect secular rhythms in both the recurrences and evolutions of a variety of human activities, including both monetary phenomena and those that do not seem to be directly associated with credit activity at first sight. We have some such examples below. By studying the interactions between bond waves and other metrics, we attempt to gain a better understanding of the dynamism of the bond wave itself.

Here, “cycle” refers to irregular dynamisms, both in magnitude and in duration.

- Regime Change in International Monetary (Currency) System

- Price Cycle

- The Private Debt Cycle: Rhythm in “Non-Neutrality of Money”

- The Fiscal Cycle: Sovereign Debt and Debt Magic

- The Political Cycle

Here, “cycle” refers to irregular dynamisms, both in magnitude and in duration.

Here, “cycle” refers to irregular dynamisms, both in magnitude and in duration

Bond wave mapping: a starting point for further inquiry

Throughout the following sections―Regime Change in International Monetary System, Price Cycle, Private Debt Cycle, Fiscal Cycle―we use a simple technique to extract information about the interactions between the bond wave and other metrics using the examples above. The scope of this technique is to draw the basis for hypotheses for further statistical inferences about the dynamisms of the bond wave. In a way, this is a discovery tool for relevant hypotheses. This technique, however, does not take us through to any conclusion; it positions us at the starting point for further legitimate and relevant inquiries.

To have the relevant questions is very important. Without the right questions, we might not reach any meaningful conclusions. The technique is simple: it requires us to cross the bond wave with the historical charts of other metrics that are relevant to subject matters of our interest. We’ll call this simple technique “bond wave mapping.” This simple method—primarily using crude data—enables us to extract hidden information about the bond wave.

In brief, the bond wave is a manifestation of socio-economic and political realities. Bond wave mapping provides a heuristic way to apply historical analogy to make inferences about our present and future based on our past.

To have the relevant questions is very important. Without the right questions, we might not reach any meaningful conclusions. The technique is simple: it requires us to cross the bond wave with the historical charts of other metrics that are relevant to subject matters of our interest. We’ll call this simple technique “bond wave mapping.” This simple method—primarily using crude data—enables us to extract hidden information about the bond wave.

In brief, the bond wave is a manifestation of socio-economic and political realities. Bond wave mapping provides a heuristic way to apply historical analogy to make inferences about our present and future based on our past.

Hypothesis, but neither prediction nor forecast

In its spirit, this attempt is one step before “forecast,” but is not “prediction.” “Forecast” is a probabilistic endeavour; “prediction” is a deterministic one. Whether we like it or not, reality is unpredictable. Therefore, we can forecast the future with probability, but rarely can we predict it with certainty.

Luckily, we are accustomed to the limitations of forecasting in our daily lives. With a weather forecast for a 60% chance of rain, we can still have a beautiful clear sky all day: with a 40% chance, there is some possibility of clear skies. Is the forecast useless? Since the 60% forecast could include the possibility of a heavy storm as well, we can better prepare for the future uncertainty per the advance forecast.

Furthermore, our endeavour is destined to be a weak form of forecast, since the limitations of secular data impose substantial constraints on us in terms of drawing statistical inferences. For the last two centuries, we can only confirm 5 bond waves. With only 5 cases, we cannot draw meaningful statistical inferences.

In a way, it is an act of forming a “hypothesis” based on empirical experiences. “Hypothesis” is one step before “forecast.” To forecast, we need a large amount of consistent and coherent data to draw statistical inferences about a “hypothesis.” However, when it comes to secular waves, the consistency and coherency of long-term data are questionable. Statistical inference based on poor-quality data can be misleading and, therefore, limited. Moreover, often, data relating to the distant past are not available. Therefore, our endeavour hardly achieves the quality that would be required of a “forecast.” Despite these weaknesses and limitations, there is merit in forming relevant hypotheses, or right questions.

Luckily, we are accustomed to the limitations of forecasting in our daily lives. With a weather forecast for a 60% chance of rain, we can still have a beautiful clear sky all day: with a 40% chance, there is some possibility of clear skies. Is the forecast useless? Since the 60% forecast could include the possibility of a heavy storm as well, we can better prepare for the future uncertainty per the advance forecast.

Furthermore, our endeavour is destined to be a weak form of forecast, since the limitations of secular data impose substantial constraints on us in terms of drawing statistical inferences. For the last two centuries, we can only confirm 5 bond waves. With only 5 cases, we cannot draw meaningful statistical inferences.

In a way, it is an act of forming a “hypothesis” based on empirical experiences. “Hypothesis” is one step before “forecast.” To forecast, we need a large amount of consistent and coherent data to draw statistical inferences about a “hypothesis.” However, when it comes to secular waves, the consistency and coherency of long-term data are questionable. Statistical inference based on poor-quality data can be misleading and, therefore, limited. Moreover, often, data relating to the distant past are not available. Therefore, our endeavour hardly achieves the quality that would be required of a “forecast.” Despite these weaknesses and limitations, there is merit in forming relevant hypotheses, or right questions.

Notes

1. The word “secular” has a variety of meanings. For our use, by “secular” we refer to long periods that can contain multiple business cycles. Referring to the “Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles, Sixth Edition,” among its variations, we refer to the following definitions in our context: Occurring or celebrated once in an age, century, etc.; living or lasting for an age or ages; process of change: having a period of enormous length, esp. of more than a year or decade. (University of Oxford, 2007, p. 2732) It is an open notion rather than a definitive one.

2. The daily volatility of interest rates in our modern times is suspected to be different from that of our ancient counterparts, which is presumed to be stale. Also, the temporal sense of investment horizon in the ancient world must differ from ours. Homer further eliminates the volatility characteristics of bond yields by taking their 10-year average.

3. In real terms, those countries can default by creating negative real interest rates: so-called “financial repression” or “inflating away.” Here, the notion of default-risk-free is strictly in nominal terms.

4. Those sovereign bonds have not been in history—and will not be in future—free from risk of default. For example, Mitchell enumerated 1781, 1798, 1917, and 1940 as examples of times when such suspicion about the default risk might well have been manifested for UK Consols (Mitchell, 1988, p. 649). Now in our time, we are compelled to sense challenges to the default risk-free status of sovereign bonds in some major advanced economies, given their high debt levels and prolonged economic stagnation under deleveraging processes.

5. In the United States, before the Great Depression, the federal government did not issue a significant amount of bonds except for the purpose of funding wars: the Civil War and WWI. Between the Civil War and WWI, the local governments were dominant issuers in the US public debt sector. In 1913, the share of the public debt was heavily weighted toward local governments: the federal government had $1,193,000; state governments had $379,000; and local governments had $4,035,000. In 1922, WWI transformed the share of public debt and the federal government became the dominant debtor, with $22,963,000; state governments had $1,131,000; and local governments had $ 8,98,000. (Carter et al., 2006)

Reference

- Carter et al. (2006). Historical statistics of the United States : earliest times to the present (Millennium Ed. ed.). (S. B. Carter, Ed.) New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Mitchell, B. R. (1988). British Historical Statistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- University of Oxford. (2007). Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles (6 ed., Vol. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Copyright © 2016 by Michio Suginoo. All rights reserved.