Series: Zeitgeist Zero Hour

Originally published: June 24, 2019

Last edited: June 30, 2019 By Michio Suginoo Introduction

How can we preserve our contemporary Liberal Representative Democracy?

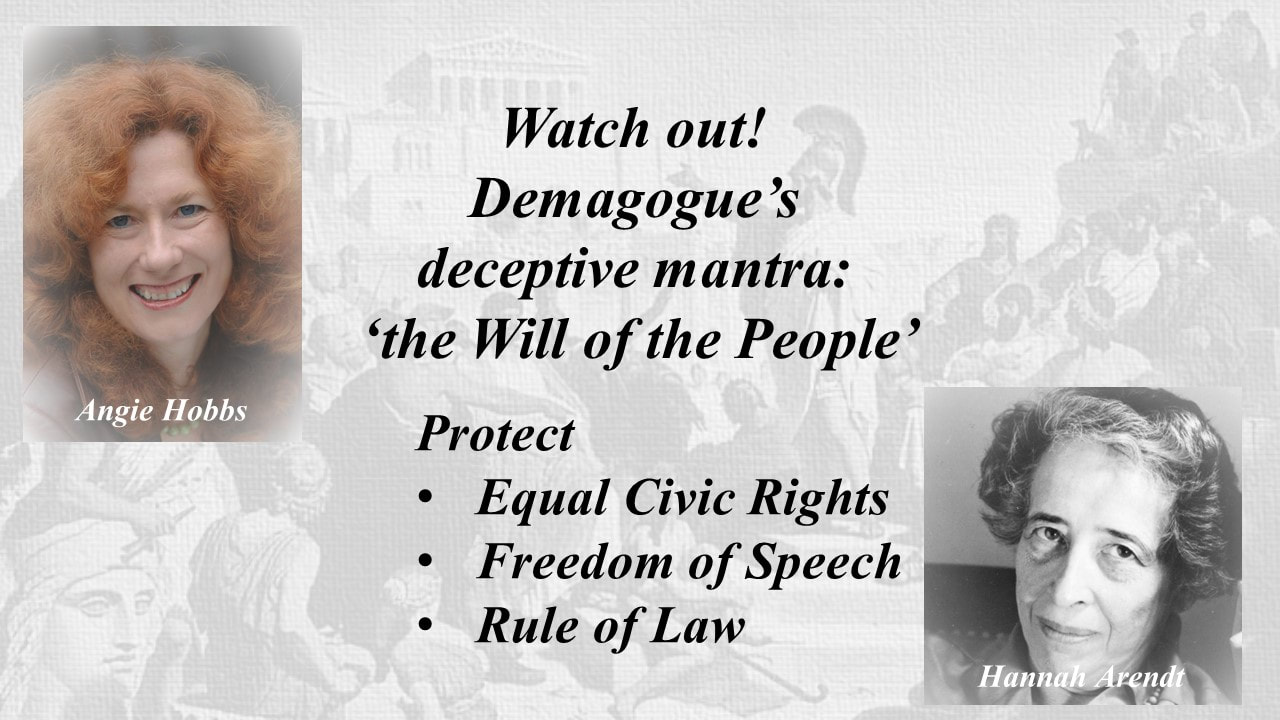

In Socrates view, the majority rule, one of the fundamental principles of democracy, paradoxically gives rise to demagogues, and subverts democracy into tyranny. Is democracy doomed to defeat itself from within? For liberal representative democracy, there are three other fundamental principles: equal civic rights, the rule of law, and freedom of expression. And the preservation of these three core principles, beyond the majority rule, is imperative for the preservation of our contemporary democracy, articulates Prof. Angie Hobbs, the Professor of the Public Understanding of Philosophy at University of Sheffield. ( The rise of the demagogue - A warning from Plato, 2017) She further warns us of the hidden danger of the seductive and deceptive mantra chanted by demagogues: ‘the will of the people’. (Democracy: a philosophical puzzle, 2017) Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), a Holocaust survivor and Jewish German thinker, based on her observation of how Adolf Hitler hijacked the post Weimar Republic democracy in Germany, left us her caveat. In our contemporary liberal representative democracy, we as voters have responsibility to maintain vigilance to defend these three core principles of liberal representative democracy, by preventing ourselves from falling prey to demagogues’ deception and from cooperating with demagogues in incubating ‘fantasy’ about ‘the will of the people’. Chapter 2, both Part 1 and Part 2, sought inspirations from the ancient wisdom of Aristotle in contemplating the preservation of democracy. When we turn to our contemporary setting, the social circumstances of our time are very different from those of Aristotle’s time in antiquity. The preservation of our contemporary democracy requires us to further incorporate specific circumstances of our time into our analysis in order to avoid anachronism. This chapter moves on to our contemporary setting and seeks inspirations for the preservation of our contemporary liberal representative democracy from these two intellects of our time. Before we begin, let us go over the risk of anachronism. Risk of Anachronism

Athenian, Roman, and our Contemporary Democratic Realities

Reflecting Aristotle’s wisdoms presented in Chapter 2, both Part 1 and Part 2, to contemplate the risk of anachronism in the context of democracy, we can compare the following three primary historical democratic achievements.

In the classical Athens, democracy meant direct democracy, which operated through direct participation in deliberative and judiciary processes in governance. Government positions were allocated in turn by random lot. The lot system eliminated the risk of corruption in the process of appointing officers: no ordinary one could manipulate the result of the lot; on the other hand, the election process can be manipulated through either bribery or favouritism. The Athenian style direct participation democracy by lot in turn was operated in the size of its free citizen body in an order of 50,000 – 60,000 in 430 BCE before the Peloponnesian War, while after the war 22,000 - 31,000. (Cartledge, 2016, p. 224)

Naturally, as the number of citizens increases, it loses its effectiveness in guaranteeing direct participation: some people cannot have an opportunity to serve in the government during their lifetime. The larger the size of citizens, the more people cannot participate in governance. In addition, a full participation of the Athenian style democracy cannot be guaranteed in a geographically widely spread state: its citizens at remote areas would find difficulty in spending time and financial resource to travel to participate in the deliberative and judiciary processes. There is a limit in the geographical area as well as in the size of the citizen body, in which the Athenian style direct democracy can effectively operate.

The ever-expanding scale of the territory and the free citizen body of the Roman Republic definitely demanded a democratic system drastically different from Athenian democracy. Not only in number, but also in the geographical area of the coverage of its citizen body did the Roman Republic far exceed the Athenians. In the Roman Republic, their most democratic constitutional achievement was a representative democratic system in the form of a mixed constitution, which allows elements of kingship (Consul), oligarchy (the Senate), and representative democracy (Tribunes and Assemblies) to co-exist and check and balance one another. Some intellects in antiquity—e.g. Cicero, Posidonius of Rhodes, and Dionysius of Halicarnassus—suggested that the Roman Republic sort of democratised the Spartan constitution for their own purpose to create their own (Rawson, 1969, pp. 104-105). Cut a long story short, in principle, they incorporated a stringent check and balance mechanism into their constitutional machinery. Nevertheless, in reality, the Roman election system gradually became infested by bribery and facouritism that perverted its voting process a priori. Our contemporary democratic achievements are in multiple forms, but might be encapsulated in one simple term, liberal representative democracy: e.g. parliamentary representative system and presidential representative system. One notable difference from these two ancestors presented above is that our contemporary liberal democracy embraces human rights and civil rights of its own citizens in principle: in practice, whether it is practiced or not is a different matter though.

|