|

BOND WAVE MAPPING: CASE STUDY 4

Mapping Government Intervention Along the Bond Wave -Fiscal (Sovereign Debt) Cycle & Debt Magic (Negative Real Yield) Cycle Originally published July 23, 2016

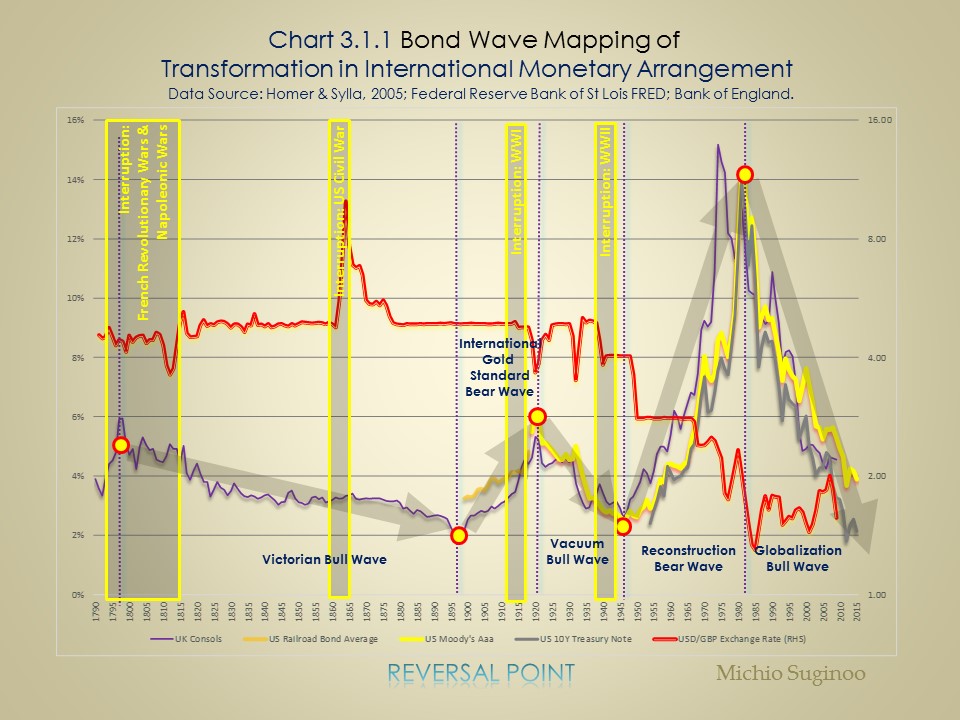

Last edited July 17, 2017 By Michio Suginoo Sidney Homer, in his chart of the centennial best credit frontier or “Homer’s Saucer,” left us a notion that the state of money has something to do with the evolution of the Western civilization. Homer’s notion extends to a life cycle of civilization. In studying the bond wave, I intend to contemplate Homer’s notion in a shorter horizon, say secular time frame. Using the bond wave, by observing a long-term transformation in the relationship between bond yields and other metrics for an extended period of time, my attempt is to capture a notion that the state of money mirrors a broader socio, political, and economic reality.

Bond wave mapping provides a heuristic approach to apply historical analogy to make inferences about our present and future based on our past. This section reviews the cycle of government intervention along the bond wave. As a reminder, the recent five bond waves are defined as follows:

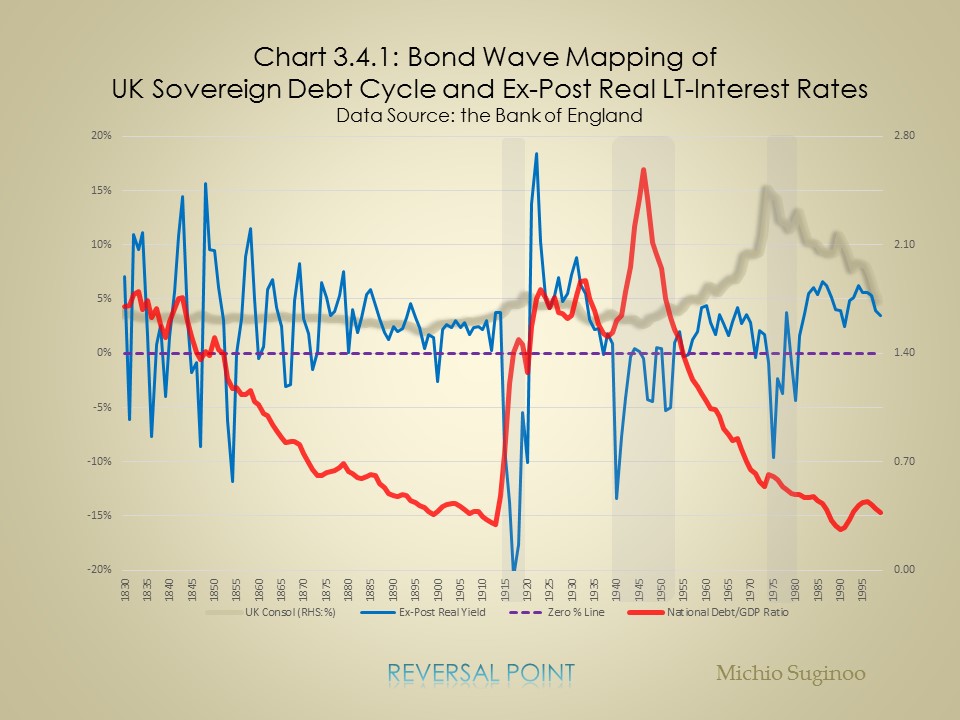

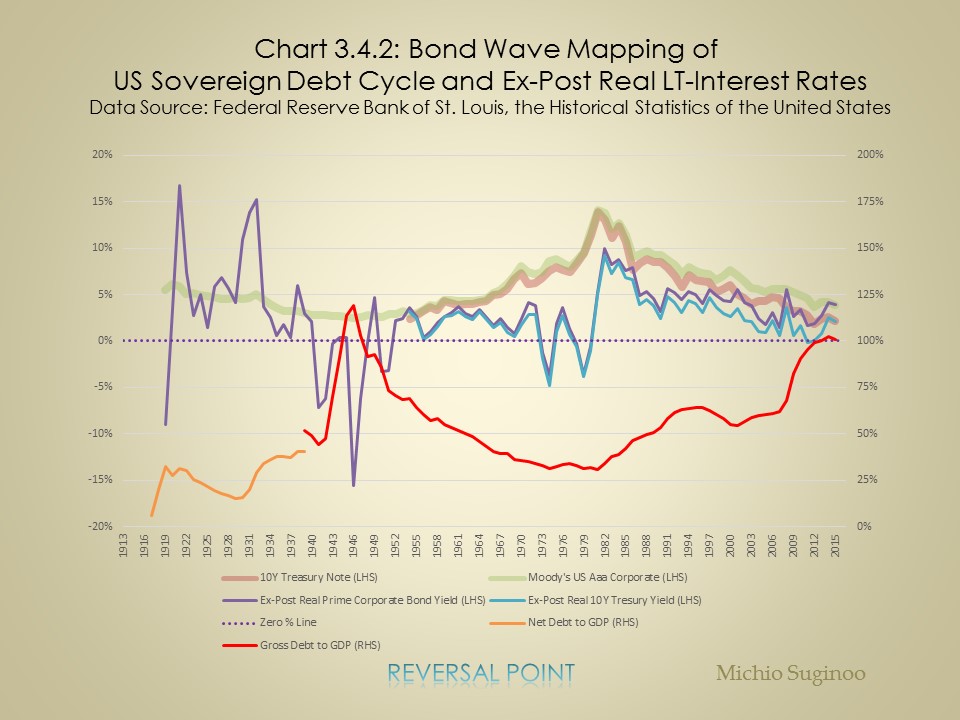

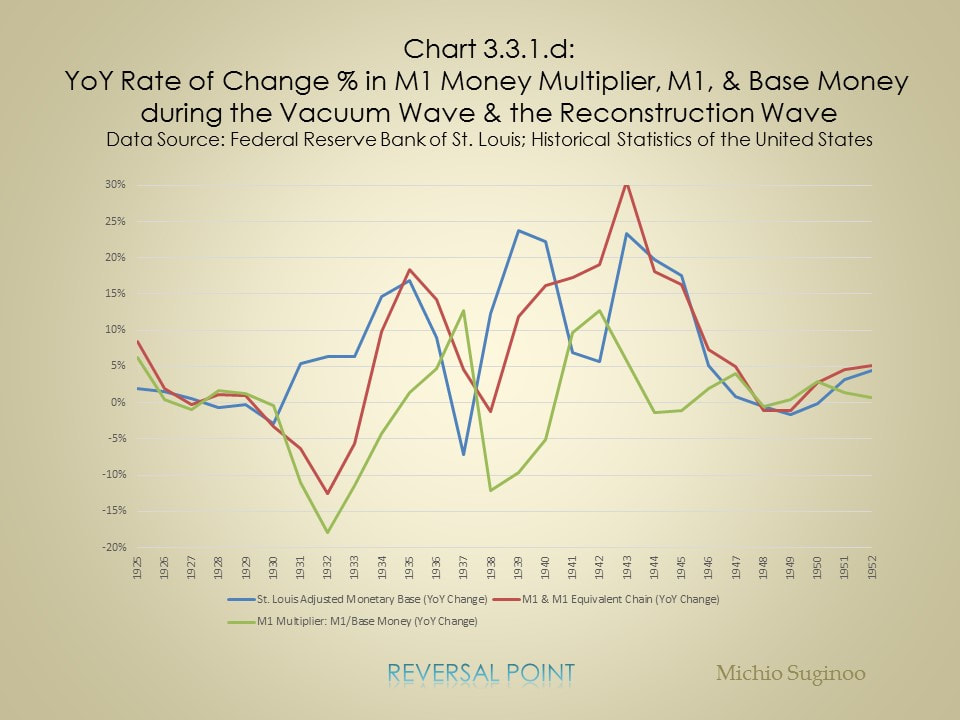

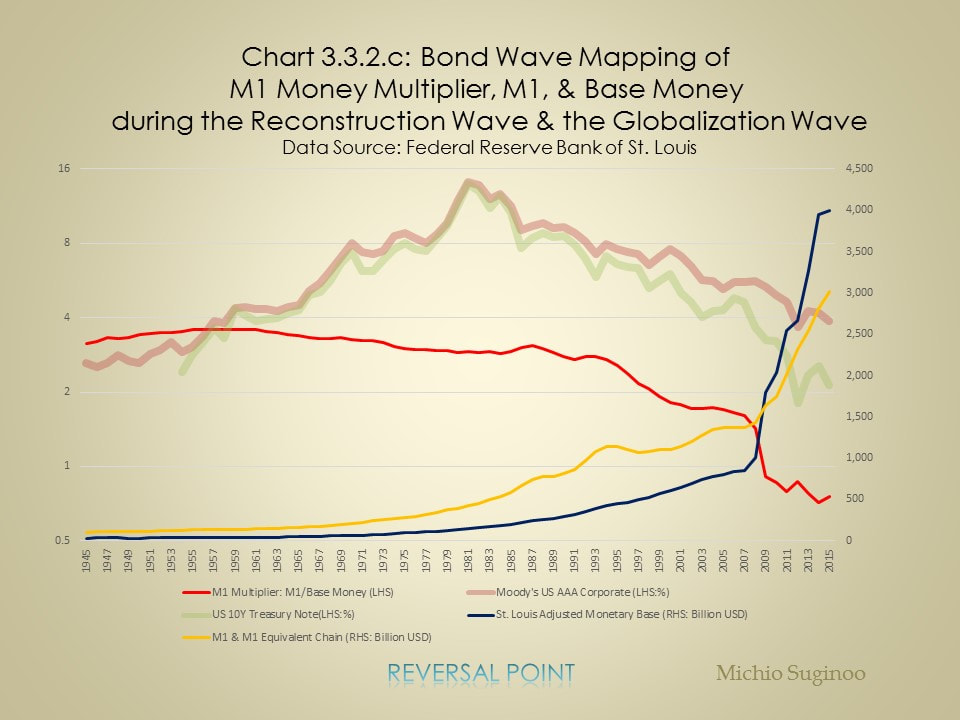

In the aftermath of Global Financial Crisis government intervention took the form of monetary expansion in a historical scale across the advanced economies. During the preceding bull wave, the Vacuum Wave, the managed economy followed economic crisis originated in the stock market crash in 1929, taking another form, fiscal expansion (the New Deal). In both cases, the advanced economies came under managed economy following the cycle of financial crisis. This reading compares these two analogous cases along the bond wave. Of course, government intervention to counter recession came into being in democracy. Before the turn of the 20th century, counter-cyclical government intervention did not exist. It is as if these two episodes imply that the combination of an economic bubble, the consequential deleveraging process, and the reactional managed economy is built into the architecture of one bull wave in the modern democratic system. Government interventions can significantly alter an economy’s dynamics. The state of our reality “cannot be reduced to [a] purely economic” system (Piketty, 2014, pp. 20, 573-574). Economy does not exist in its pure form, but as a by-product of a variety of interactions with political and social activities—regulations, fiscal and monetary policy, taxation, environmental issues, labour movements, etc. The bond wave mapping indicates some recurrent notions in the emergence of government interventions during the late stage of the recent bull waves. As an example, the New Deal Policy was introduced from 1933 to 37 during the late stage of the Vacuum Wave; and a series of massive monetary expansions were taken from 2008 to 2016 during the late stage of the Globalization Wave. Although government interventions in economy can take place at any moment, these two episodes have special characteristics to distinguish themselves from others in the context of the bond wave. Both episodes share a special context in terms of the bond wave. These emerged as responses to financial crises that occurred in the middle of bull bond waves. And these measures were mobilised in the context of democracy. Prior to the 20th Century—pre-democratic era—this sort of measure was least likely taken in response to financial crises, This reading overviews the transformation of government interventions along the bond wave. Why do we care about such things? Positioning at the middle of the late bull wave, we might be able to learn about the prospect in the behaviour of government interventions, from the empirical episodes comparable in the bond wave context. The Sovereign Debt Cycle Major significant historical transformations in fiscal behaviour can be captured by historical records of sovereign debt. Charts 3.4.1 and 3.4.2 illustrate the trajectories of sovereign debt-to-GDP ratios and real interest rates along the bond wave for the United Kingdom and the United States, respectively.

When we look for a similar bond wave location in the previous bull bond wave to our time, a series of government interventions took place in the United States during the period after Black Thursday during the Vacuum Wave:

Toward the end of this period, the bond yield made a reversal. Does the empirical experience tell us anything about our future?

|